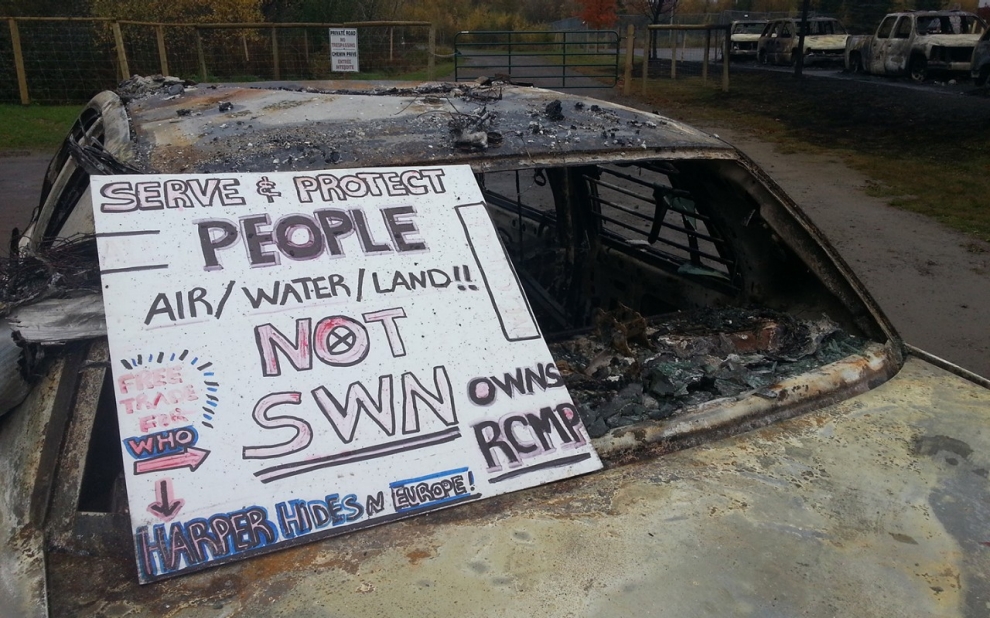

REXTON, N.B. – A day after an anti-fracking protest here turned violent, with 40 people arrested and torched police cars sending clouds of black smoke into the air, aboriginal protesters huddled around a fire pit at the site of their anti-fracking encampment, sipping coffee and discussing their next move. A tense calm hung in the air while, down the road, local high school students gawked at the row of burnt-out vehicles towed to a vacant lot.

Canada's national police force, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, charged into the area early Thursday, hoping to break up a weekslong protest where demonstrators blocked the roads, denying SWN Resources Canada, a Texas-based shale gas company, the chance to retrieve its testing equipment from a storage compound.

Of the people arrested, nine are expected to spend the weekend in jail. Police used pepper-spray and rubber bullets to enforce the court-ordered injunction, according to protesters, while officers seized a number of weapons, including guns, explosive devices and knives.

The conflict, whose dramatic images spread quickly through social media, has heightened tensions between New Brunswick's First Nations and the provincial government, and thrust the debate over the environmental impact of shale gas exploration back into the spotlight.

It has also led to protests elsewhere in Canada, with the First Nation group Idle No More saying that at least 40 events were planned throughout the country. It also prompted calls for calm from Canada's justice minister, Peter MacKay.

On Friday, demonstrators at the encampment said the battle was far from over.

John Levi, a leading protester who is known as the war chief for the Elsipogtog First Nation, which is located a 15-minute drive from the encampment, said protesters would track down the equipment and block the company from testing for shale gas reserves elsewhere.

“If they're in New Brunswick, we'll find them,” said Levi, expressing concern about the environmental impact of hydraulic fracking on the water system and soil.

While Levi and many protesters are wholly opposed to shale gas development, other First Nations leaders in the province have expressed openness to the possibility if they have a greater stake in the process and more environmental precautions are taken.

Meanwhile, even though workers for SWN Resources Canada succeeded in taking out the equipment on Thursday, protesters showed no signs of clearing out of the area.

The group was still blocking half of the single-lane highway with traffic cones and posters in the shape of stop signs declaring “Say No to Shale Gas.”

Some of the tents and tarps, however, appeared to have been trampled, and some of the larger signs were left in a ditch.

Many of the protesters were young and appeared organized.

First Nations members wearing yellow safety vests, and others dressed in army fatigues, directed traffic through the narrowed road. And a pair of portable toilets had been installed on both sides of the lane.

As they gathered around a central fire pit, several protesters declined to speak to journalists on the record, saying they didn't feel they were given a fair hearing in the media.

New Brunswick's Premier David Alward has argued the shale gas industry can be developed in a safe and sustainable way, helping to bring jobs and revenue to the economically-struggling province.

Alward met with Elsipogtog Chief Arren Sock in Fredericton, along with some of his councillors and advisors, on Friday afternoon. Sock was among those arrested on Thursday.

The meeting between the two sides ended late in the evening with both agreeing to have representatives meet early next week, and another meeting between the two leaders to follow.

SWN Resources issued a statement on Friday saying its employees “are dedicated to the safety of people and the environment” and stressed that it is only in the early stages of exploration in New Brunswick.

Many at the site said they weren't optimistic the conflict would end anytime soon.

For one Elsipogtog First Nations woman, it brought back bad memories of the 1990 Oka Crisis, a months-long land dispute in Quebec that pitted Mohawk people against the town of Oka.

“I don't want to see that happen again,” said Marilyn Simon-Ingram, a 59-year-old teacher, who was visibly shaken after touring the damage at the encampment.

The police action was excessive, she said, adding that she's fully behind the protests, because you “can't eat a dollar bill, and you can't drink a dollar bill either.”

Over the past few weeks, the standoff near Rexton had steadily gained attention, with First Nations coming in from Nova Scotia.

Alward told reporters Friday the police action was in part a response to “outside influences.”

At a news conference, the RCMP defended their actions, contending if that the protests had become unsafe and that lives could be in danger.

The protest near Rexton has also attracted non-native protesters.

Emma Stropel and two friends hopped in the car on Thursday, and drove over 500 miles to get from Montreal, Quebec to the protest site. They brought a tent and plan to stay at least a few days.

She said police action is “often more heavy-handed” when a protest involves First Nations communities.

Not everyone, however, is opposed to shale gas development in New Brunswick. Polls show New Brunswickers are split over the issue, with many optimistic about its potential economic benefits.

In Rexton, a group of local residents gathered at the site of the charred cop-cars, marvelling at how their normally quiet town of about 900 had come under the spotlight. Images of flaming cop cars and camouflaged police armed with rifles quickly spread on social media, and shocked many local residents.

“Obviously, emotions got out of control,” said Matt Kenney, who lives in Rexton, and is concerned about the environmental impact of shale gas – and skeptical of the long-term environmental benefits.

Error

Sorry, your comment was not saved due to a technical problem. Please try again later or using a different browser.