PHILADELPHIA — While Philadelphia universities have pulled back on their expansion into poor, mostly minority neighborhoods, gentrification they helped initiate has led to a development boom that is ratcheting up tension in the city.

Along streets in West Philadelphia where the black middle class was once rooted and along avenues in North Philadelphia that until recently were most known for 1964’s protests and riots over police brutality in the black community, new buildings are rising. Some are built by the universities, but most are other construction projects, namely new or renovated apartment buildings that have used Temple University, the University of Pennsylvania and Drexel University as anchors for new developments and even newly rebranded neighborhoods.

James Johnson, the head barber at Tommy's Barber Shop in North Philadelphia, just a few blocks from Temple University, has seen his neighborhood change dramatically in the last two decades.

The dilapidated row houses are being replaced with fancy condos and housing catering to students, and there’s an increased police presence on the city streets. Johnson says he's happy the housing is getting fixed up, but gentrification of his city has been a “double-edged sword.”

“In the last five years, we had an 80 percent jump in rent,” at the barber shop, he said. “It’s a concern that’s lurking over you.”

The names used by residents for rapidly gentrifying areas of the city speak to the development’s perceived source. For example, Google Maps caused an uproar earlier this year when it labeled the area around Cecil B. Moore Avenue, a historically black and low-income community, TempleTown. The company quickly heeded community demands to change the neighborhood name on its maps. The gentrification taking place in West Philadelphia is often referred to as Penntrification.

“They’re creating enclaves of whiteness,” said Chad Dion Lassiter, a social worker, lifelong Philadelphia resident and the president of Black Men at Penn School of Social Work, an alumni network. “When communities of color can’t come to your library, can’t come to your lawn, when you situate security booths around the perimeter of your campus and keep people out … you’re dismantling a community to create a university as a community.”

Having universities cause or exacerbate gentrification isn’t unique to Philadelphia. Columbia University has for years been embroiled in controversy as it has expanded into the predominantly black neighborhood of Harlem. The University of Chicago is mired in a similar conflict with the surrounding community over its expansion.

In Philadelphia the sheer number of universities and other institutions like hospitals and research centers within the city’s limits and the level of poverty in the surrounding communities compound the tension.

The city is home to the University of Pennsylvania (enrollment: 25,000), Temple University (37,600 students) and Drexel University (25,500), as well as the smaller Philadelphia University, Saint Joseph’s University, University of the Sciences and many others.

In West Philadelphia, which abuts the University of Pennsylvania and Drexel, nearly 50 percent of people live below the poverty line, according to city data. In North Philadelphia, which surrounds Temple University, over 50 percent of people do.

All three large universities are undertaking major expansions. Temple announced a $1.2 billion expansion in 2010. Penn is in the midst of $4 billion expansion. Drexel, once a small school with a large commuter population, has rapidly expanded in the last decade and has about $2 billion worth of construction planned.

Responding to community concerns, the three have promised to keep most of the development contained to land they already own.

“Ten years ago, when we were putting together the Temple 20/20 plan, neighbors told us they wanted more students to live on campus,” university spokesman Brandon Lausch said via email. “As a result, we built the largest residential complex in Temple's history, with beds for nearly 1,300 students on campus.”

Penn spokesman Ron Ozio said, “For decades, Penn has been growing with the neighborhood in mind” and avoiding projects in residential areas. Brian Keech, Drexel’s senior vice president in the office of government and community relations, said the university was primarily looking to develop in the University City area of Philadelphia.

Still, some projects have become symbolic of the changing neighborhood dynamics in the city. When Temple bought a high school building that had been shuttered by the city over the summer, it sparked protests. Drexel has come under fire for purchasing another closed city school, which it plans to turn into a high-rise “work-study-shop-and-hang-out-district.”

“When I was a child, the university was our neighbor,” said Robert Carter, who grew up in a neighborhood of West Philadelphia called the Bottom, which Penn bought out in the 1940s and now sits on top of. Carter is the associate director of the university’s African American Resource Center. “This wasn't University City. The university was in the community. Now the university is dictating what the community looks like.”

But much of the development in Philadelphia is beyond the universities’ control. For every development project the universities have created, a plethora of others have been created by private developers — namely high-end stores, private student housing and entertainment venues. And critics say those places are often created with less sensitivity to their neighborhoods.

“The issue is the developers,” said Keech. “What they’re trying to do is speculate, but they do it because the universities are successful.”

The pressure placed on neighborhoods surrounding universities is compounded by the city’s growth. After years of decline, the city has added 64,000 people since 2006, in some years growing by more than 1 percent. Home prices are increasing rapidly, and some of the most popular neighborhoods for new construction are in the areas surrounding the city’s three biggest universities.

The stress on low-income residents of Philadelphia is exacerbated by the city’s property tax system, overhauled in 2013, which bases taxes not on home sale prices but on the value the city assigns to each property. That value is based on a few factors, including surrounding home values. That means a house bought for $20,000 decades ago that’s surrounded by houses now worth $200,000 could be assessed at $200,000. The city passed legislation that caps longtime residents’ tax bills — often referred to as gentrification relief. But even with that tax dispensation, there’s concern that the money being poured into neighborhoods near universities will inevitably lead to displacement.

Jannie Blackwell, a councilman who has represented University City and some of the poorest sections of West Philadelphia since 1992, has watched some of the areas transform. The Mantua neighborhood in West Philadelphia went from being one of the poorest and most neglected in the city to being a Promise Zone to being on the gentrification frontier.

“It looks like now, after we worked so hard to help residents there and invested so many dollars, they won’t be able to take advantage because they’re gentrifying people out,” he said. “After all this, to help the neighborhood survive and turn around, and people can’t afford to stay there.”

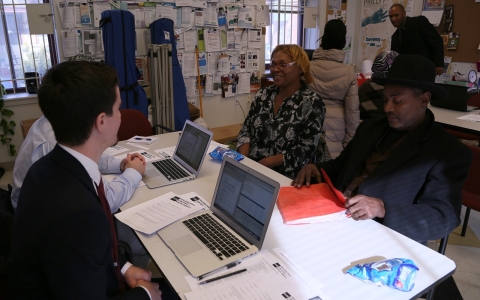

The three universities have made efforts to reach out to the community while they expand. Temple has created advisory panels with community members that the university says it consults during development. Drexel has built the Dornsife Center for Neighborhood Partnerships in West Philadelphia. There residents can interact with the university administration, faculty and students and get legal and tax help.

But residents and activists say these well-intentioned gestures do little to ensure the neighborhoods stay affordable.

“With all the major development going on with these core institutions, the pressure is on,” said Herman Bingham, an electrician and a resident of Mantua. “Every vacant lot has been zapped up. It’s not about getting along with the universities. It’s about not being displaced.”

In a city with poverty rates among the nation’s highest, many corner stores rely on food stamp customers for business

Philadelphia residents seeking expungement say they’re denied jobs and housing over crimes they often didn’t commit

Public and private stakeholders are pushing to further capitalize on the Marcellus Shale fracking boom

The architects of welfare reform want millions of poor Americans to work for food – or else

Error

Sorry, your comment was not saved due to a technical problem. Please try again later or using a different browser.