Though we must now use the past tense when speaking of the charismatic and controversial Colombian Nobel Prize–winning writer Gabriel García Márquez, who died Thursday at age 87, the more than 50 million copies of his books, published in nearly 40 different languages, mean that his work will live forever.

Novelist, screenwriter, short-story writer and journalist, Gabriel José de la Concordia García Márquez lived with his family in Mexico City since the early 1960s due to the political turmoil in Colombia, though in recent years he spent increasingly more time in his home in Cartagena de Indias.

García Márquez’s legacy includes the acclaimed novels “Autumn of the Patriarch” (1975), “Chronicle of a Death Foretold” (1981), “Love in the Time of Cholera” (1988), which was adapted to the screen in 2007, the story collection “No One Writes to the Colonel” (1968) and the piece of reportage “News of a Kidnapping” (1997). He also wrote a book of memoirs, “Living to Tell the Tale” (2003), spurred by a bout with lymphatic cancer that he survived. In 2012, he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.

His masterpiece, “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” published in 1967, remains one of the most enchanting and beloved works of 20th century literature, an icon of magical realism and Latin American literature that captivates new generations of readers time and again.

The term “magical realism” was coined to describe the poetic thrust of reality, in which supernatural elements such as fairy tale and folklore are placed within a poker-faced objective reality. It was the perfect form for relating the phantasmagorical political tumult in Latin America during the 1960s and 1970s, when the novel is set. “One Hundred Years of Solitude” tells the saga of the Buendía family and the foundation of the fictional town of Macondo. It has become a centerpiece of the literary feast that was the “Latin American boom,” when the rest of the world finally paid attention to an emerging generation of writers coming out of a formerly untapped region; the Argentinian Julio Cortázar; the Nobel-winning Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa; the Cuban in exile Guillermo Cabrera Infante; and the Mexican Carlos Fuentes, among others.

As a Nobel laureate, García Márquez enjoyed rock star status. He won the award in 1982, arguably one of the most popular Nobel winners ever. He called Faulkner his “master” and said his fictional Macondo was fashioned after Yoknapatawpha, Faulkner's fictional county. He often remarked on the epiphany of reading the first sentence of Jorge Luis Borges’ translation of Franz Kafka’s story “The Metamorphosis”:

“As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect.”

Yet the writer was famously anti-intellectual and hated theoretical explanations of his work, preferring a more intuitive approach to the art of the novel.

Ultimately, he explained, his biggest inspiration was his grandmother, whom he grew up with in the tropics of Colombia and whose storytelling technique lingers and breathes life into his pages. For example, the yellow butterflies that follow his character Mauricio Babilonia and alight as silent angels on his sickbed: García Márquez told the story about a time when an electrician came to their house with a strange belt that he used to climb the poles. His grandmother swatted at a yellow butterfly, saying that every time the man showed up, a butterfly appeared.

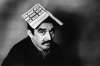

The writer was many things to many people; Gabriel to his family, García Márquez to international crowds, Gabo endearingly to many friends and millions of Latin American readers, and Gabito to his inner circle. The mustachioed Colombian, who looked more like a boxer than a writer, was a son of the Caribbean and its sensuous fantasy. He was born in the town of Aracataca in 1927, and grew up with his maternal grandparents until leaving for school in the capital, Bogotá. His grandfather was a colonel who killed a man in a duel and had three legitimate children in addition to several illegitimate ones scattered around town. After he’d studied law and worked as a journalist in El Espectador, the political unrest sent García Márquez back to the coast, to the town of Cartagena de Indias, where he left his studies and got down to writing. He wanted to stay close to the real world, a journalist who wrote fiction. “Leaf Storm,” his first novella, was written in 1955, when he was only 27 years old.

More than anything else, however, García Márquez wrote to please his friends, who often had nothing to do with the world of literature. He had a very peculiar, inexplicable attraction to power. He loved being close to it. His controversial friendship with Fidel Castro was considered shameful and inexcusable. In his memoirs, Reinaldo Arenas bitterly mentions the hypocrisy of it. Some speculate that his strange fascination for the embodiment of the Latin American caudillo was a way of supplanting his grandfather’s figure.

García Márquez’s politics were also the source of a very public tit-for-tat with Susan Sontag in 2003, when she was in Colombia for the Bogotá Book Fair. At the time, the Cuban government had imprisoned a number of dissidents and the press was anxious for statements. She said: “I’ve seen how a declared communist even today, like José Saramago, rejects the monstrosity of what happened in Cuba. So I ask myself, ‘What is García Márquez going to say?’ I’m afraid my answer is: He’s not going to say a word. I can’t excuse him for not raising his voice. The value of his voice could help many individuals who are struggling.” García Márquez replied: “My friendship with Castro allows me to get dissidents off the island.” Which Sontag called “weak and ridiculous.”

There was also a famous scrape between the two Nobel laureates Vargas Llosa and García Márquez that could hardly have happened anywhere else. They had both lived in Barcelona in the early 1970s and had been close friends, until García Márquez tried to seduce Vargas Llosa’s wife, Patricia. The next time they met was at a film premiere in Mexico City. The Peruvian Nobelist cried out “traitor,” and right-hooked the Colombian Nobelist so hard he nearly knocked him out cold. García Márquez stayed down, and the fight ended there. He sported a black eye for days.

García Márquez is survived by his wife, Mercedes Barcha, and his sons Rodrigo (a filmmaker who has directed episodes of “The Sopranos” and “Six Feet Under”) and Gonzalo (a graphic designer).

The writer bequeathed words to clothe the myth and imagination of the southern shores of the Caribbean, bringing epic significance to the joys and tragedies of his people’s lives. In his Nobel speech he wrote: “Poets and beggars, musicians and prophets, warriors and scoundrels, all creatures of that unbridled reality, we have had to ask but little of imagination, for our crucial problem has been a lack of conventional means to render our lives believable.” And continued: “On a day like today, my master William Faulkner said, 'I decline to accept the end of man.' This, my friends, is the crux of our solitude.”

SLIDESHOW: GABRIEL GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ, 1927 - 2014

Error

Sorry, your comment was not saved due to a technical problem. Please try again later or using a different browser.