For decades, Americans have taken for granted that every website, service and app is treated equally by their Internet service providers. This principle, dubbed Net neutrality, is what allows startups and large corporations to compete on a level playing field, ensuring that Internet providers can’t pick winners and losers by blocking websites or having some load faster than others.

But Internet advocates warn that under a new set of rules scheduled to be introduced by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) on Thursday, this guarantee will be effectively gone, allowing Internet service providers to give prioritized access to websites that pay a premium — and slower service to everyone else.

The FCC proposal would be welcome news for broadband Internet providers like Verizon, Comcast and Time Warner Cable, some of which have already begun experimenting with charging online services for fast-lane access to their customers. FCC chairman Tom Wheeler has tried to reassure critics that these arrangements would be strictly regulated on a case-by-case basis. But a growing coalition of Net neutrality advocates, tech companies, investors and members of Congress have slammed the anticipated proposal, calling it “a threat to the Internet” as a domain for free speech and commerce.

“It’s going to be ruinous for innovation online,” said April Glaser, an activist with the Electronic Frontier Foundation. “It directs people away from newer, innovative services that might not be able to afford that price tier.”

The reason Net neutrality is now endangered has to do with a decision by the FCC in 2002. The commission, under pressure from telecom lobbyists, neglected to designate broadband Internet providers as telecommunications services — a legal distinction under the Telecommunications Act for utilities whose only role is to transport information.

Broadband providers control what’s known as the last mile, the network cables that transmit data to and from individuals, homes and businesses. Instead of being classified as utilities, publicly regulated providers of essential services such as water or electricity, the providers were placed under a much looser set of rules, in a category called information services. In essence, the FCC decided to treat Internet providers more like Amazon and Google than like utility companies such as ConEd and PG&E.

That pivotal decision put the FCC’s efforts to enforce Net neutrality on shaky legal ground. Since Net neutrality principles were introduced in 2005, a judge has on two occasions struck down rules that prevented Internet providers from prioritizing some companies’ traffic over others, ruling that the FCC didn’t have authority because it hadn’t made the providers subject to common-carrier rules.

The second time, in January of this year, the judge acknowledged that “broadband providers represent a threat to Internet openness and could act in ways that would ultimately inhibit the speed and extent of future broadband deployment.” But because the FCC had not properly classified Internet providers as telecommunications services, the court ruled it could not stop the providers from discriminating against traffic.

Wheeler, a former telecom lobbyist, said last week that he will “not allow some companies to force Internet users into a slow lane so that others with special privileges can have superior service.” But according to reports citing people who have seen the proposal, the rules to be revealed on Thursday will create a policy that allows providers to strike deals with online services such as Netflix that put them in a difficult position: either pay fees in exchange for prioritized delivery of their content on the network or allow customers to suffer significantly slower speeds.

In other words, in addition to charging customers for Internet access, broadband providers would be able to charge individual content providers like Facebook, Google and Netflix for enhanced ability to reach their customers — as long as the broadband providers agree to transparency requirements and the deals are deemed commercially reasonable by the FCC.

Net neutrality advocates say the only way to guarantee a level playing field is for the FCC to reclassify Internet service providers as telecommunications services. But to do so, the FCC would have to argue that Internet providers are utilities because consumers choose them only on the basis of speed and price — and that’s a politically toxic argument.

The telecom lobby is prepared to fight tooth and nail to maintain the status quo. It wields so much political power that former FCC Chairman Michael Powell — who issued the original Net neutrality principles in 2005 and is currently CEO of the National Cable and Telecommunications Association — has said that any attempt to reclassify broadband under the common-carrier rules would be “World War III.”

Comcast, one of the louder Internet service providers lobbying for what they call paid prioritization, has argued that it’s reasonable to charge content providers because bandwidth-heavy streaming services like Netflix put additional strain on its network. The company also places blame on backbone transit providers — intermediary companies like Level 3, Cogent and Tata that connect local broadband providers internationally — claiming that those companies should be paying Comcast for the imbalanced traffic ratio caused by Netflix use. (In other words, Netflix users often download far more data than they upload.) The argument is that Comcast needs to upgrade its capacity to serve Netflix content to its customers and that the video-streaming business and the backbone providers should foot the bill.

This is an inversion of the way Internet providers currently bill. Today customers — whether an individual, a family or a content provider like Google — pay Internet service providers like Comcast a monthly connection fee, and the ISP in turn pays backbone providers, regardless of traffic ratios. With Net neutrality out of the picture and almost monopoly status in many areas of the United States, Comcast and others will be able to collect fees from parties at the middle and ends of the network — including the backbone providers and content providers like Netflix and Amazon.

Facing slower service, Netflix has grudgingly entered into paid interconnection (or peering) agreements with both Comcast and Verizon to ensure its content reaches customers reliably on those networks. The deals involve providers’ charging Netflix for separate “private roads” between Netflix’s servers and the providers’ facilities. Even though there is no practical difference between this and a fast lane, these agreements can be used as a loophole because they technically don’t violate Net neutrality. For this reason, Internet advocates say that any future Net neutrality rules must take peering agreements into account.

Tim Wu

law professor, who coined “Net neutrality”

Meanwhile, large Silicon Valley companies that owe their success to the Internet’s nondiscriminating nature insist that a level playing field is essential for innovation to emerge.

Last Wednesday, a group of nearly 150 tech companies sent a letter to the FCC saying that rules allowing broadband providers to discriminate and impose tolls on content providers represent “a grave threat to the Internet.”

“This commission should take the necessary steps to ensure that the Internet remains an open platform for speech and commerce so that America continues to lead the world in technology markets,” wrote the group, which includes tech giants like Google, Facebook, Ebay, Twitter and Microsoft.

Three years ago, a similar coalition of tech companies helped catalyze the massive online protests that stopped SOPA, the anti-piracy bill that would have let private companies meddle with the Internet’s infrastructure to block copyrighted material. Those companies could put similar pressure behind preserving Net neutrality, especially as Obama meets with tech executives to raise campaign cash. But their statements haven’t listed any specific demands, and it’s unclear whether their support will go beyond strategic lip service.

Others have started to think about more long-term solutions. Internet advocates like law professor Susan Crawford, a former special assistant to Obama on science and technology, have proposed circumventing the ISPs entirely by encouraging cities to build their own high-speed fiber networks.

That path has hurdles of its own, however: In large part because of lobbying from companies like AT&T, CenturyLink and Time Warner Cable, 20 U.S. cities have restrictions or outright bans on building municipal broadband networks — including in states with underserved rural areas like North Carolina where telecoms are unable or unwilling to provide service themselves. Wheeler has said he seeks to eliminate those restrictions.

Meanwhile, large Silicon Valley companies who owe their success to the Internet's non-discriminating nature insist that a level playing field is essential for fresh innovation to emerge.

Last Wednesday, a group of nearly 150 tech companies sent a letter to the FCC saying that rules allowing broadband providers to discriminate and impose tolls on content providers represent “a grave threat to the Internet.”

"This Commission should take the necessary steps to ensure that the internet remains an open platform for speech and commerce so that America continues to lead the world in technology markets," wrote the group, which includes tech giants like Google, Facebook, Ebay, Twitter, and Microsoft.

Three years ago, a similar coalition of tech companies helped catalyze the massive online protests that stopped SOPA, the anti-piracy bill that would have let private companies meddle with the Internet's infrastructure to block copyrighted material. Those companies could put similar pressure behind preserving net neutrality, especially as President Obama meets with tech executives to raise campaign cash. But their statements haven't listed any specific demands, and it's unclear whether their support will go beyond strategic lip service.

Others have started to think about more long-term solutions. Internet advocates like law professor Susan Crawford, a former Special Assistant to President Obama on science and technology, have proposed circumventing the ISPs entirely by encouraging cities to build their own high-speed fiber networks.

That path has hurdles of its own, however: Due in large part to lobbying from companies like AT&T, CenturyLink and Time Warner Cable, 20 US cities currently have restrictions or outright bans on building municipal broadband networks — including in states with underserved rural areas like North Carolina where telecoms are unable or unwilling to provide service themselves. The FCC's Wheeler has previously stated he seeks to eliminate those restrictions.

Meanwhile, large Silicon Valley companies who owe their success to the Internet's non-discriminating nature insist that a level playing field is essential for fresh innovation to emerge.

Last Wednesday, a group of nearly 150 tech companies sent a letter to the FCC saying that rules allowing broadband providers to discriminate and impose tolls on content providers represent “a grave threat to the Internet.”

"This Commission should take the necessary steps to ensure that the internet remains an open platform for speech and commerce so that America continues to lead the world in technology markets," wrote the group, which includes tech giants like Google, Facebook, Ebay, Twitter, and Microsoft.

Three years ago, a similar coalition of tech companies helped catalyze the massive online protests that stopped SOPA, the anti-piracy bill that would have let private companies meddle with the Internet's infrastructure to block copyrighted material. Those companies could put similar pressure behind preserving net neutrality, especially as President Obama meets with tech executives to raise campaign cash. But their statements haven't listed any specific demands, and it's unclear whether their support will go beyond strategic lip service.

Others have started to think about more long-term solutions. Internet advocates like law professor Susan Crawford, a former Special Assistant to President Obama on science and technology, have proposed circumventing the ISPs entirely by encouraging cities to build their own high-speed fiber networks.

That path has hurdles of its own, however: Due in large part to lobbying from companies like AT&T, CenturyLink and Time Warner Cable, 20 US cities currently have restrictions or outright bans on building municipal broadband networks — including in states with underserved rural areas like North Carolina where telecoms are unable or unwilling to provide service themselves. The FCC's Wheeler has previously stated he seeks to eliminate those restrictions.

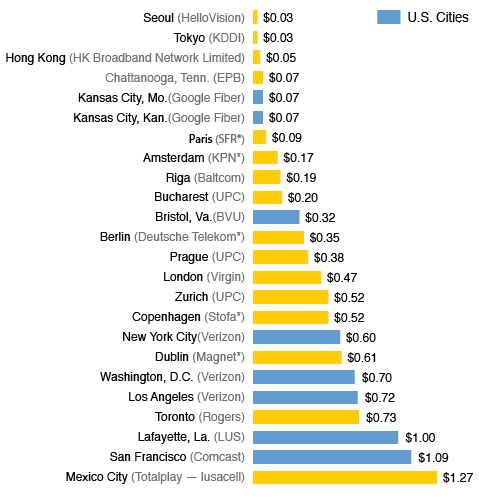

U.S. Cities tend to pay more per megabyte/second than other similarly wired cities around the world

*Offers included additional bundled services.

Advocates say losing Net neutrality would mean two things for consumers: higher prices and slower speeds. Prices for consumers would go up as content providers like Netflix pass the costs of their fast lane access on to them. It’s difficult say to how large the price hikes might be, however.

On average, U.S. cities already have much higher prices and slower speeds for Internet service compared with many cities in other industrialized nations. A 2013 study by the Open Technology Institute shows that the fastest Internet service in Seoul, South Korea, can be had for about $36 per month, whereas Verizon’s fastest connection in New York City costs $299.99 per month and offers less than half the speed.

One exception is Chattanooga, Tenn., where a municipal broadband provider has lowered the cost of 1,000-megabit-per-second Internet service from $350 to $70 per month. In U.S. cities without municipal broadband, the highest speeds available for the same price average about 1/20th the speed.

Tim Wu, a law professor and former Federal Trade Commission adviser who coined the term “Net neutrality,” warned last year that without Net neutrality rules, “we can expect a fight that will serve no one’s interests and will ultimately stick consumers with Internet bills that rise with the same speed as cable television’s.”

Startups and small businesses that can’t pay the toll for speedy service could also be harmed. New companies that aren’t in the fast lane could easily lose customers to a competitor’s much faster offerings. Also, giant media companies like NBC that have merged with broadband providers like Comcast would have an incentive to prioritize their own content over others; if the proposed merger of NBC-Comcast and Time Warner Cable is approved, the resulting conglomerate would reach approximately one-third of U.S. homes, giving it more bargaining power over which services get faster speeds.

“If an ISP is behaving badly, customers should be able to vote with their feet,” said Glaser, the EFF activist. “People should have the choice to take their business elsewhere to get better service, but we don’t see a competitive environment like that [in the United States].”

Details of the FCC’s plan are still not set in stone. So far, two FCC commissioners, citing concerns with Wheeler’s plan, have asked him to delay addressing the Net neutrality issue. The commission will also be accepting public comments on the proposal after its presentation to the public. But unless it is substantially different from how it was reported, the final proposal will likely mean a fundamental shift for the Internet as a platform for free speech and innovation. With protesters already camped out in front of the FCC’s offices in Washington, calls for Net neutrality are bound to get much louder before they quiet down forever.

Broadband companies might be able to deal faster traffic for companies that can afford it on 'case-by-case' basis

Commission says even though court struck down provisions it sought, decision provides 'blueprint' for new regulations

Net neutrality ruling a major blow to communities of color

Error

Sorry, your comment was not saved due to a technical problem. Please try again later or using a different browser.