Source: Numbers for above charts are totals for Pennsylvania counties inside the Susquehanna River basin from United States Department of Agriculture, Census of Agriculture, 2012, 2007 and 2002.

Gregory Martin, a poultry expert who teaches at Penn State’s College of Agricultural Sciences, in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, the seat of Lancaster County, is skeptical that there is a connection between estrogen from agricultural pollution and intersex fish. “I just don’t see that happening,” he said. “Nice study, but I think we need to look at more of the picture.”

But Vicki Blazer, the lead author on the study, says the spike in livestock is significant.

They are “raising more animals in the same space,” she said. “As those numbers increase, obviously the nutrients and estrogens and other hormones they excrete increases as well.”

Today, Pennsylvania is the nation’s fifth-largest producer of milk, third largest of eggs and the top producer of mushrooms, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

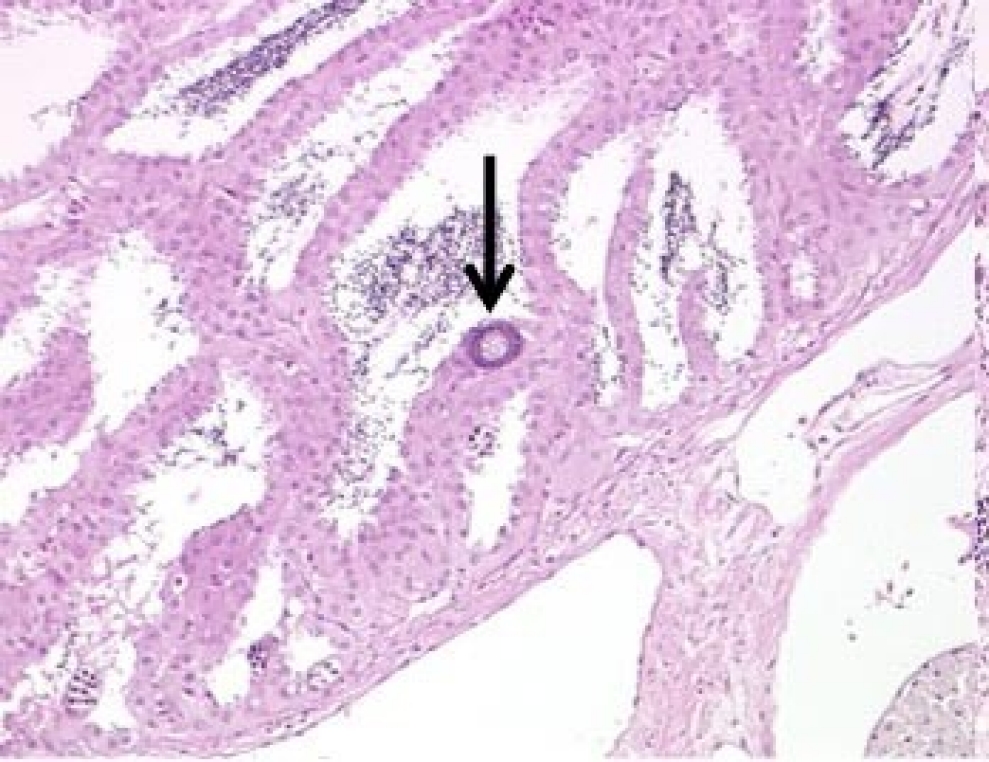

Intersex fish have been a worldwide phenomenon for two decades, and scientists have found them in the U.K., Germany, Italy, South Africa and Japan. After a massive die-off of smallmouth bass in 2003 in the Potomac River, another tributary of the Chesapeake Bay, scientists discovered that many of those ill fish were also intersex.

Most of the sickened bass found in the Susquehanna’s summertime surveys are just a few months old. Disease in fish so young suggests that their immune systems are being hurt early, scientists say. Smallmouth bass spawn in the spring, the same season when the most water runs into rivers from ranches and farms because of melting snow and heavy rains. Male bass build nests by sweeping silt off the river bottom with their fins so that females may lay their eggs. Then the eggs sit there, and often become coated with a thin layer of silt, which, the report says, contains “higher numbers and concentrations of estrogenic compounds” than the water.

“Estrogens are involved in a multitude of health and disease endpoints,” said John A. McLachlan a professor in the School of Pharmacology at Tulane University. “Not the least in immune dysfunction.”

Representatives of the agriculture industry say they have taken steps to reduce overall pollution, as mandated by state and federal laws. Also, they say, the intersex-fish report is far from conclusive.

“Studies like this have to be viewed with the understanding that correlations or associations do not necessarily equal causations,” said Richard Carnevale, vice president at the Animal Health Institute, an agricultural lobbying group.

Estrogen from human waste also enters rivers through sewage and industrial-waste treatment facilities, of which there are some 5,000 on the Ohio, Delaware and Susquehanna Rivers, according to the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection. This can include synthetic estrogens from contraceptive and hormone replacement pills, which take longer to break down, scientists say. Though the water treatment process removes estrogen, there is no state standard for how much may remain, a spokeswoman from the DEP said. Also, no facilities have been upgraded to specifically remove estrogen.

Tracey Woodruff

reproductive-science professor

But the proportion of estrogen in waterways that results from agricultural pollution is generally more than 90 percent, while the proportion from human waste is less than 10 percent, said Tracey Woodruff, a reproductive-science professor at the University of California, San Francisco, who co-authored a 2010 report on estrogen pollution.

“Human waste is at least treated,” she said. “Cows don’t use toilets, and a lactating pregnant cow, for example, produces a lot of estrogen.”

The USGS report shows no correlation between wastewater-treatment facilities and the number of nearby intersex fish, but it does show that the testes of the intersex fish nearby have larger clusters of egg cells than those of bass from elsewhere in the river.

Agricultural pollution has also been cited as a likely source of another recent scourge on the Susquehanna River: blooms of toxic levels of algae. The algae feed on phosphates and nitrates, two nutrients in industrial fertilizers. When the algae proliferate, at times stretching bank to bank, biologists say, they suck oxygen from the water and leave little for fish. (A similar algae bloom in Lake Erie has now imperiled drinking water in Toledo, Ohio).

Agriculture “keeps coming up,” said Geoff Smith, Susquehanna River biologist for the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission. “It’s frustrating.”

Source: River basin geography and waterways from the Susquehanna River Basin Commission. Sampling locations from Reproductive health indicators of fishes from Pennsylvania watersheds: association with chemicals of emerging concern," published June 17, 2014.

On Wednesday, Smith finished the latest census of smallmouth bass in the Susquehanna and found numbers still low and many fish covered with sores and lesions. In 2013 nearly half of all smallmouth bass in the river showed signs of disease, the highest percentage yet.

(In 2011 the conservation nonprofit organization American Rivers listed the Susquehanna as the most endangered river in the nation, not because of pollution from wastewater or agriculture, but because of the potential for contamination from fracking. In 2010 the conservation group American Rivers named the Upper Delaware River the nation’s most endangered for the same reason. Both of these rivers flow above a huge reserve of natural gas called the Marcellus Shale, which has been tapped by thousands of natural gas wells in the last decade.)

The Environmental Protection Agency has taken broad steps to improve the water quality in the Chesapeake Bay and, by association the Susquehanna River, including raising standards for water-treatment facilities and limiting the amount of sediment that may be sloughed off from municipal storm-water systems and from agricultural operations, across the Chesapeake Bay drainage basin. Critics say this is not enough.

“We’re focused on improving water quality with the hope that in conjunction with everything else going on that it will have a positive impact on the ecosystem as a whole,” said Tom Wenz, a spokesman for the EPA’s Chesapeake Bay Program Office. “None of these issues is going to be solved through looking at just one aspect.”

But Arway, of the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission, said state and federal leaders must write a cleanup plan specifically for the Susquehanna River, for which news of intersex fish is only the latest in a litany of problems.

“You need a cleanup plan for the river that’s different than the one for the bay,” he said. “I don’t want to be director when the last bass is caught out of the Susquehanna River.”

Error

Sorry, your comment was not saved due to a technical problem. Please try again later or using a different browser.