Michael Nelson, professor of environmental philosophy and ethics at Oregon State University, says it’s time to start thinking more critically about the wilderness ethic. He has studied the writing and correspondences of the founders of the wilderness movement, including ecologists Aldo Leopold and Olaus Murie.

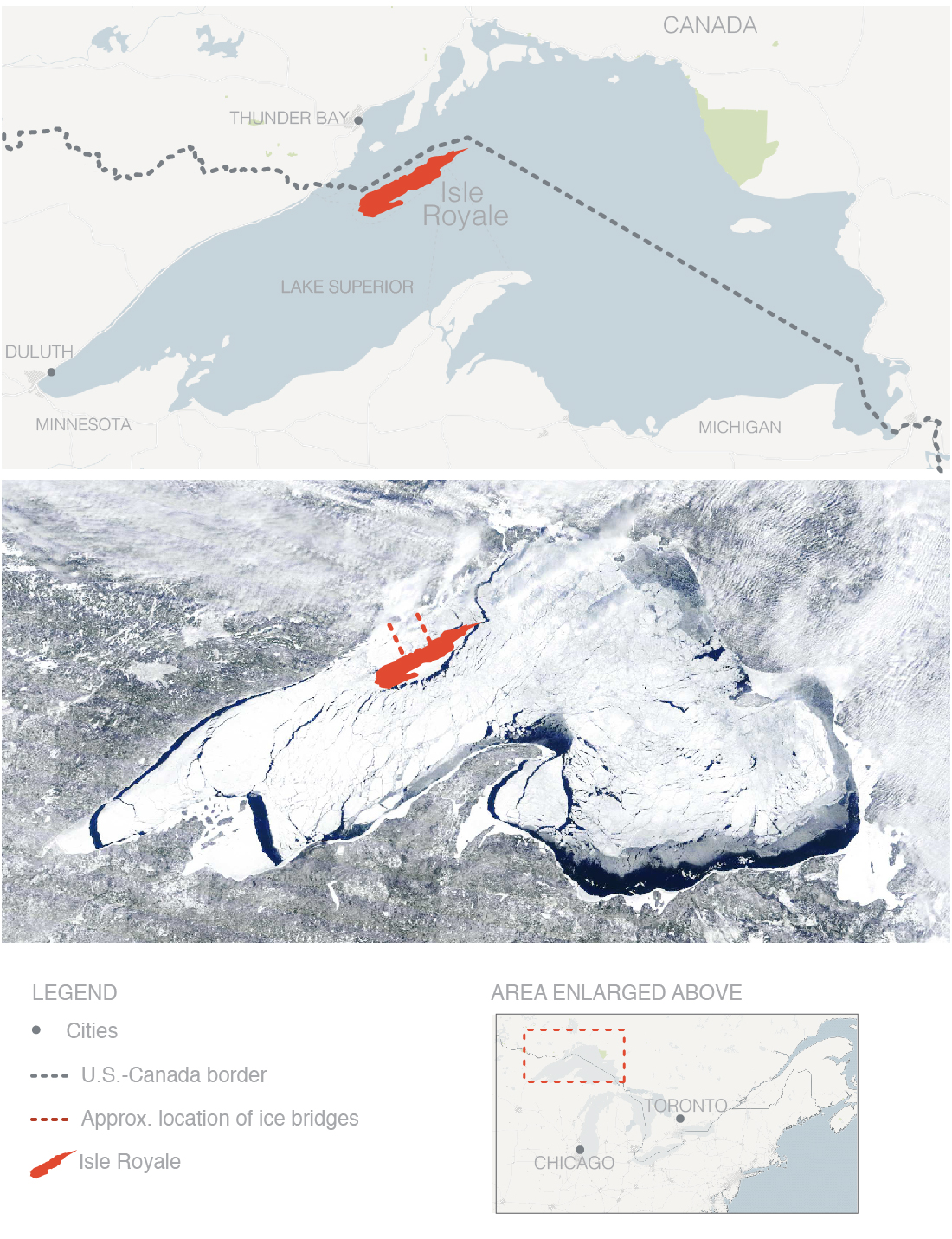

In the mid-1940s, Leopold and Murie proposed transporting wolves to Isle Royale in order to control the island’s huge moose herd, which, lacking any predators, had been going through major boom-bust cycles since colonizing the island (also via the ice bridge) in the early 1900s. Moose numbers would grow quickly thanks to the island’s ample vegetation and then, as food sources like the balsam fir were over-browsed, the moose would suffer from malnourishment and have low breeding success. Once the population fell precipitously, the plants would regain a foothold and moose numbers would grow along with that recovery — until they grew too much and the boom-bust cycle restarted. Adding a predator, such as wolves, to the ecosystem would keep the moose numbers from booming and, therefore, would keep vegetation levels stable.

Ultimately, Leopold and Murie — who had convinced the National Park Service to bring wolves to the island —did not need to intervene. Around 1949, at least two wolves came onto the island of their own accord and found there a feast. During the decades in which this predator-prey relationship has been studied, the wolf and moose populations have grown and shrunk in response to each other. Now, with wolf numbers shrinking, the moose population has doubled over the past three years. Without the predator to keep it in check, moose would likely re-enter boom-bust cycles.

“I think there are going to be times — and there probably always have been times — where human intervention might promote ecosystem health, and it might also protect the ability to have something that we would call a wilderness,” says Nelson. “There is no demand on us to be wise or prudent when you just equate wilderness with nonintervention."

Error

Sorry, your comment was not saved due to a technical problem. Please try again later or using a different browser.