Last month Don McIntosh, a journalist and friend of mine in Portland, Ore., posted on Facebook that his half brother Daniel McIntosh had just been sentenced to at least 10 years in prison for selling 954 kilograms of marijuana and money laundering as part of a 16-member pot-selling ring. “Our nation’s drug and mandatory minimum sentencing laws are monstrously unjust,” he wrote. “His mom, his wife and three kids are also punished by this prison sentence.”

It could have been worse. Had federal prosecutors prevailed in convicting Daniel McIntosh of distributing more than 1,000 kilograms, his previous drug convictions would have triggered a sentence of mandatory life without parole. Facing the judge before sentencing, McIntosh reflected on what such a long term would mean. “When you love your children as much as I love mine, sir,” he said, “two days away from them ... 10 years, 20 years ... I don’t know how my mind can even comprehend that.”

The drug war is in its fifth decade and on its eighth president, yet what befell McIntosh for trafficking a drug that many Americans consider less harmful than alcohol still defies comprehension.

The root of extreme sentencing is legislative: Eighty-three percent of those serving life without parole for a nonviolent offense as of 2012 received a mandatory minimum sentence prescribed by law. Judges protest the harsh sentences even as they hand them down.

President Barack Obama, the inheritor of a war on drugs created by his predecessors, has criticized excessive sentences. But he has done little to undo the damage. In particular, he has commuted very few harsh sentences. As with pardons, which forgive a crime, commutation power is absolutely granted to him by the U.S. Constitution (except in the case of an elected official’s impeachment). While pardons typically make life better for people who have already served their sentences, commutations can free those currently languishing behind bars. On Monday, Attorney General Eric Holder announced a new initiative aimed at increasing the number of clemency applications reviewed and granted, but media reports suggest that it might be small-scale or piecemeal. Obama should send a more forceful message by issuing a huge number of commutations — and by doing so now.

Long sentences have become routine in this country’s interminable war on drugs. According to a major American Civil Liberties Union report (PDF) released last year, as of 2012, at least 3,278 nonviolent offenders were serving life without parole, including 2,074 in federal prisons. Many will die in prison for minor drug crimes, ever since three-strikes and habitual offender laws mandated life sentences for small-time convictions.

The system is cruel and, without question, unusual. Only 20 percent of countries sentence anyone to life without parole, and few hand out such sentences to nonviolent offenders. China and Pakistan, frequent targets of human rights criticism from the U.S., review life sentences after 25 years’ imprisonment. Americans are the most incarcerated people on earth: 2.4 million are behind bars in U.S. prisons and jails.

On April 15, White House counsel Kathryn Ruemmler announced that the Obama administration would take decisive action to commute the sentences of those serving excessively harsh sentences. But reform advocates who are part of a coalition called Clemency Project 2014 remain skeptical that the Department of Justice will override harsh sentences sought by their own prosecutors. What is clear is that Congress and state legislatures are moving too slowly to raze a vast, expensive system of mass incarceration constructed over decades of tough-on-crime politicking. Advocates are thus increasingly putting pressure on Obama and governors to exercise their power to free nonviolent lifers by commuting their sentences.

When federal clemency has received attention in the past it has typically been because presidents have controversially granted it to political allies.

President Gerald Ford pardoned his predecessor Richard Nixon. Bill Clinton pardoned oil trader Marc Rich during his final hours in office even though Rich was a fugitive at the time. (Rich’s former wife had made large contributions to the Democratic Party and to the Clinton Library.) George W. Bush commuted the sentence of I. Lewis Libby, a former chief of staff of then–Vice President Dick Cheney who was convicted of lying to federal investigators.

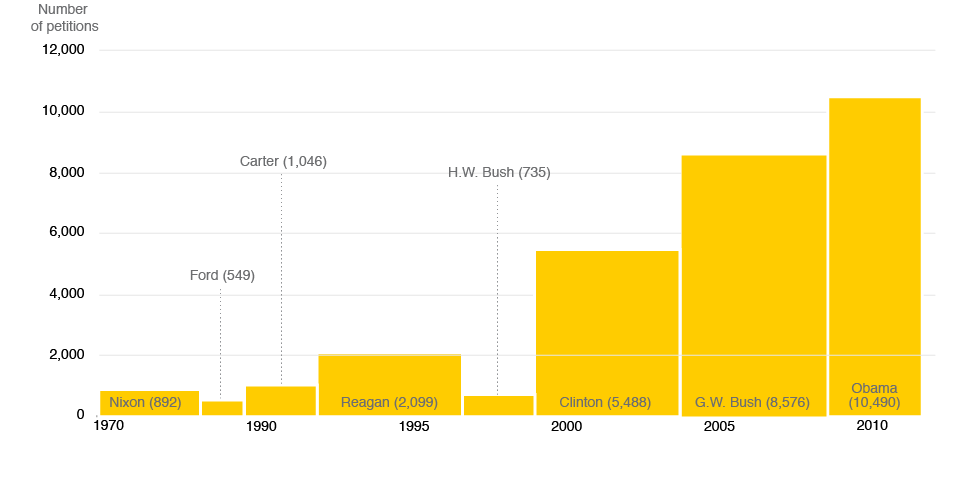

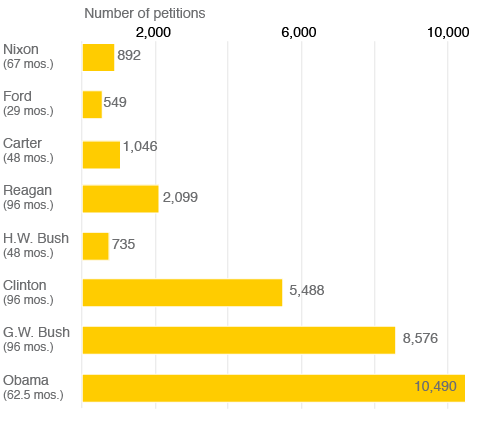

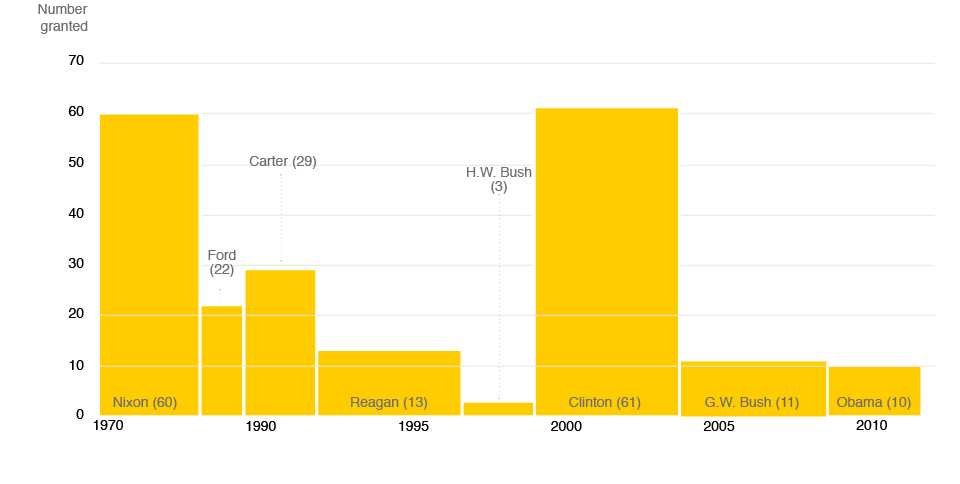

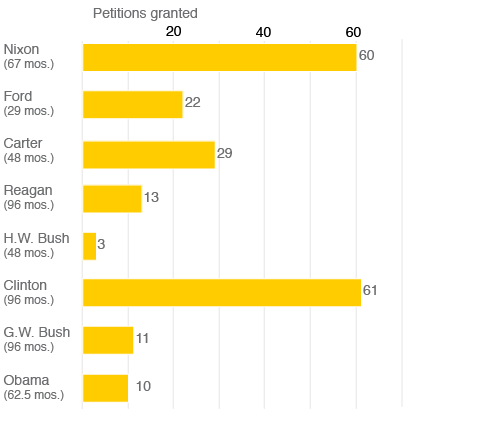

For most lifers, though, pardons and commutations are not a likely option. President Lyndon Johnson commuted 226 sentences, Nixon 60, Ford 22, Jimmy Carter 29, Ronald Reagan 13, George H.W. Bush 3, Clinton 61, George W. Bush 11. As sentences lengthened starting in the 1980s, the number of petitions for commutation skyrocketed, from 892 under Nixon to 8,576 under George W. Bush. During that period, the percentage of commutation requests granted declined from nearly 7 percent to one-tenth of 1 percent. Obama has already received at least 10,490. Thus far, he has granted only 10.

Source: Department of Justice clemency statistics.

In December, Obama commuted the sentences of eight nonviolent convicts serving long sentences for crack cocaine. Many, he noted, would already have been freed had they been sentenced under the 2010 Fair Sentencing Act, which narrowed (but failed to eliminate) the disparity between crack and powder cocaine sentences. On April 15, the president commuted the sentence of a man who was serving 42 additional months because of a typo on a court document. Yet prior to December, Obama had commuted just one sentence, and Justice Department’s pardons attorney, Ronald L. Rodgers, has been heavily criticized for running a pardons office that recommends reprieve for precious few — including those favored by the department’s inspector general.

Freeing nonviolent lifers would not end mass incarceration, and commuting only the most sympathetic or extreme cases focuses attention on the exception rather than the rule. But Obama could embrace criminal justice reform without provoking much Republican protest (though skepticism from some corners is inevitable). There is significant consensus across the political spectrum: Fiscal conservative Grover Norquist and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People both agree that mass incarceration has spiraled out of control. Tellingly, Texas, perhaps the paragon of tough justice in the U.S., has led the way in downsizing its state prison population.

If Obama decided to commute the sentences of the 2,000-odd nonviolent federal lifers, he would distinguish himself from his predecessors, who waited until the last moment to dole out political favors, and shrewdly focus the nation’s attention on undoing a system that took years of hysterical legislation to create.

Asked about the low number of commutations last year, Holder told reporters, “We are at year five I guess of eight, so I would say hold on.”

These drug-war prisoners now belong to Obama. Many have already waited far too long.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera America's editorial policy.

Error

Sorry, your comment was not saved due to a technical problem. Please try again later or using a different browser.