An extraordinary shift in wages paid to American workers took place from 2000 to 2012, a change that holds powerful lessons about the minimum wage, government policy and unions.

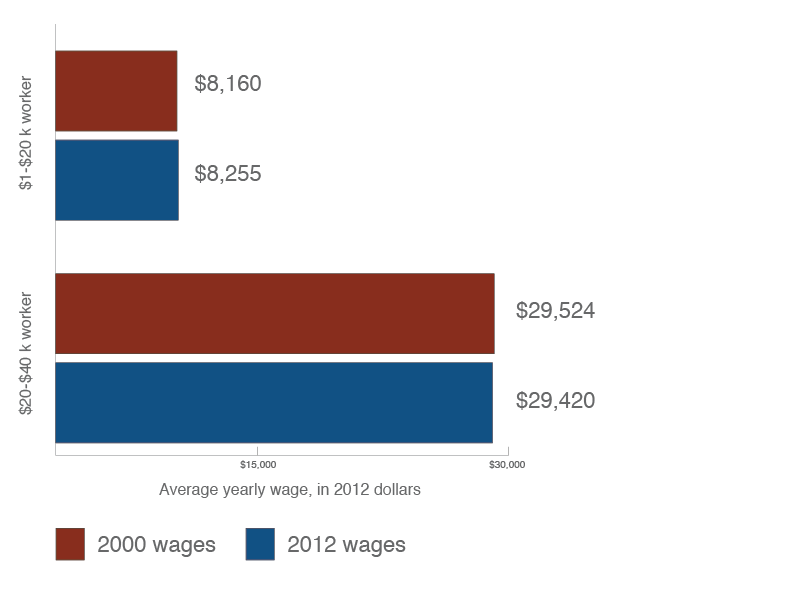

The lowest-paid workers — those making less than $20,000 a year — saw their average pay rise by more than the rate of inflation. There were nearly 61 million workers in this group in 2012, and they averaged $8,255 in wages annually. Compared with the year 2000, that was a real increase of $95, or 1.2 percent.

That’s not much, but it’s better than what happened to workers just above them, those earning $20,000 to $40,000. Their 2012 average wage slipped a tad, down $104, to $29,420, from 2000.

Many factors are at work in this shift, but one appears crucial: minimum wage laws.

Workers at the bottom enjoyed on average a real pay raise despite a surplus of unemployed people and a weak economy. These bottom-of-the-wage-ladder workers, generally unrepresented by unions, are powerless.

But government can be a proxy for unions. In this case the wage hike was signed by none other than President George W. Bush, helped by 82 House Republicans and all but four Senate Republicans.

In 2007, Bush signed into law increases in the minimum wage that took effect in 2007, 2008 and 2009. Each raised the minimum by 70 cents, lifting it to $7.25 an hour. Before Bush signed the increases into law, minimum wage workers had gone a decade with no increase. By 2007, inflation had reduced the value of their hourly pay to 77 cents on the 1997 dollar.

Commentators often note how inflation robs retirees on fixed incomes, but less frequently about how it ravages the pocketbooks of the lowest-paid workers, many of whom then turn to the government for food stamps, medical care and other costs that society must bear.

Because of Bush’s signature, the 2012 minimum wage was 40 percent higher than in 2000. That is significantly more than the 33 percent increase in prices caused by inflation over those dozen years.

Typically such comparisons cannot be made because the federal government reports most data by fixed income categories, which are not adjusted for inflation.

But while reviewing wage statistics published on the Social Security Administration website, I recalled a delightfully convenient fact from the Bureau of Labor Statistics inflation tables: To adjust 2000 prices to 2012, you multiply by 1.333. That means $15,000 in the year 2000 is equivalent to $20,000 in 2012.

That meant, in turn, that I could compare workers making under $15,000 in 2000 with those making $20,000 in 2012. The same is true for $30,000 to $40,000, and for $75,000 to $100,000 and so on, as long as the 2012 category is a third higher.

However, there is no comparable way to assess workers at $50,000 in 2000, for example, with those at $66,666 in 2012, because no such category exists in the official data.

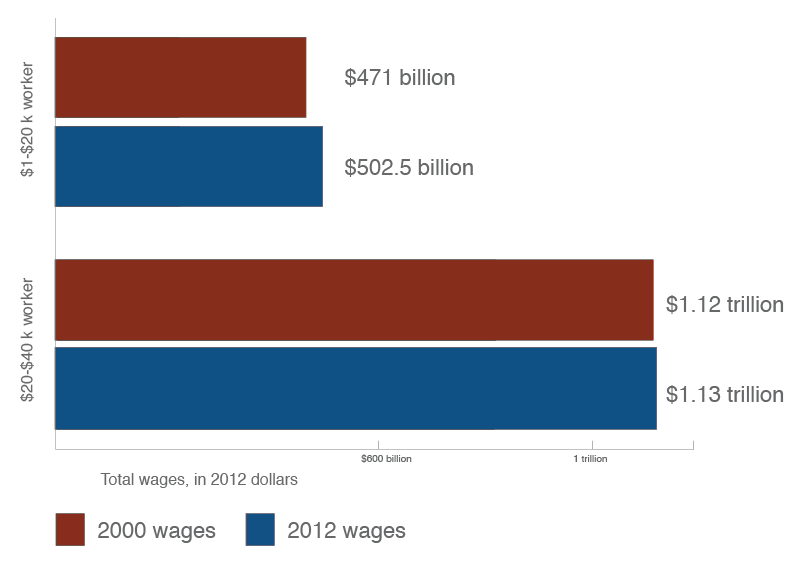

Still, this analysis covers a huge swath of workers. In 2012 nearly 61 million workers, or 39 percent of the workforce, made less than $20,000. In 2000 almost exactly the same share of the workforce made $15,000 or less.

Only a minority of these lowest-paid workers earned the minimum wage. But those who made up to about $2 an hour above the minimum also benefited from its increase, as their pay also rose because of what labor economists call the spillover effect, one of the best-documented and most studied areas of how minimum wage increases affect the economy. Raising the minimum wage in steps until it reaches $15 in today’s money would benefit workers making as much as $20 an hour because of this spillover effect.

To understand the concept, imagine you are a minimum wage worker and get promoted to shift supervisor. Your added responsibilities bring an extra 50 cents an hour.

Then Congress and the president raise the minimum wage by 50 cents. To maintain that premium for your added responsibilities, your employer will raise your wage by the mandated amount and may even bump it by a bit more, say 55 cents extra an hour.

When I was a 17-year-old minimum wage worker, the absentee owner of a Baskin-Robbins franchise promoted me to store manager and gave me a desperately appreciated extra 15 cents per hour. Then the federal minimum wage rose by 15 cents, and the owner said the crew would get the same as me — until I started to untie my apron, at which point he agreed to retain my 15-cent-an-hour premium.

And how did the franchise cover the cost of the higher wages? I tried to make store operations more efficient to shave costs, and the owner raised the price of a single scoop by a penny, to 11 cents. That increase was a little less than the 12 percent hike in the minimum wage. We suffered no loss of customers.

Spillover effects weaken the farther one’s pay is above the minimum. For a worker making $15 an hour, the spillover effect from increasing the minimum wage is essentially zero.

But the spillover effect still benefits a large number of workers. Consider someone who works 50 weeks at $15 an hour, or $30,000 a year. More than half of U.S. workers — 53 percent in 2012 — make $30,000 or less. Consequently, if cities, counties, states and Uncle Sam raise the minimum wage in steps until it is $15 in today’s dollars, the spillover would improve the pay of the almost 2 out of 3 workers who make less than $20 an hour.

There is no free lunch, of course. But neither economics nor higher pay is a zero-sum game, as opponents of the minimum wage often assume. Higher pay draws more people into the labor market, and it means workers have more to spend on goods and services, which creates more demand to hire more workers as well as generating more profits for business owners. It also means less demand for food stamps and other government benefits, easing taxpayer burdens, even as prices rise a bit to cover higher labor costs.

Seven years ago, a Republican president who famously said his base was “the haves and the have-mores” signed into law a raise for the lowest-paid workers. In the House of Representatives, 82 Republicans voted to raise the minimum wage. That kind of bipartisanship today would do America a lot of good.

Source: Social Security Administration and Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera America's editorial policy.

Error

Sorry, your comment was not saved due to a technical problem. Please try again later or using a different browser.