There was a lot of hurt in the music world in 2014. It started in January, when folk icon and civil rights activist Pete Seeger died at the age of 94. In July, both punk music and the classical world suffered blows just days apart with the death first of Tommy Ramone, the drummer and co-founder of the seminal punk band the Ramones, and then Lorin Maazel, the legendary conductor who directed more than 200 orchestras, including for many years the New York Philharmonic. Ramone was 65; Maazel was 84.

They weren’t the only losses in the music world this year, of course. The following list is to guide you toward gifted musicians of all genres who might not have received the headlines Seeger, Ramone and Maazel did, but whose memory and music are worth noting.

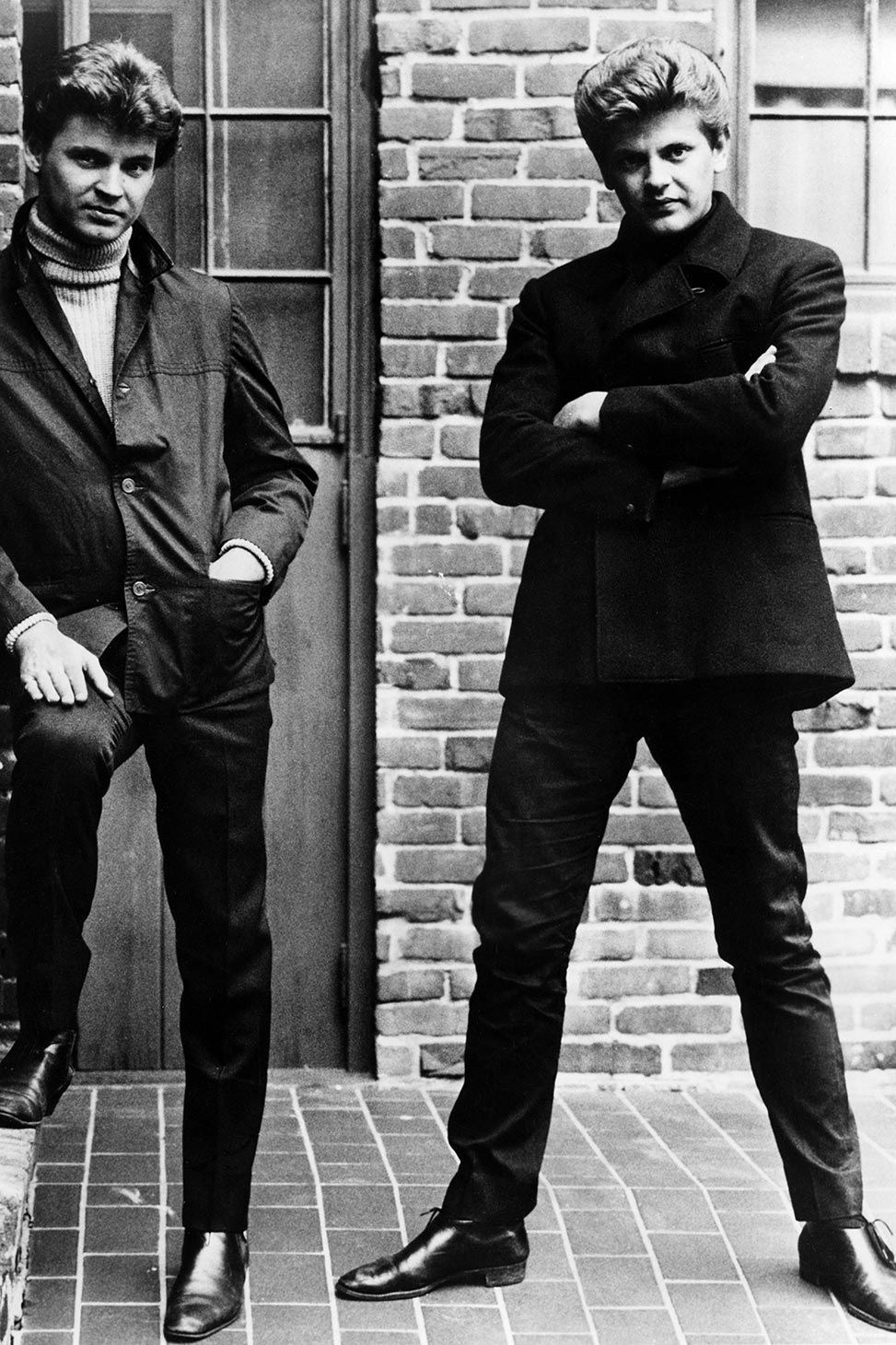

Phil Everly (pictured on the right), who with his brother, Don, made up one of the greatest vocal duos of all time, died on January 3. The Everly Brothers scored 15 Top 10 hits in the late ’50s and early ’60s, including “Bye Bye Love”, “Wake Up, Little Susie” and “When Will I Be Loved.” Featuring the same unearthly singing ability as their predecessors in country music the Louvin Brothers, Phil and Don set a standard of close-knit harmony reflected later by Simon & Garfunkel and the Beatles, as well as just about every pop vocal group in the 1960s and 1970s. “You guided my musical development, my life,” wrote Art Garfunkel to Phil in tribute. “I sought a partner because you showed me what two can do.”

The Everly Brothers seldom performed together in the last quarter-century, something Don reflected in his own statement: “Our love was and will always be deeper than any earthly differences we might have had,” he wrote. “The world will be mourning an Everly Brother, but I’m mourning my brother Phil Everly.” Such was the duo’s influence that Paul McCartney contributed a song to their 1984 reunion album.

When Alexander Ivashkin performed — say, a Prokofiev sonata for solo cello — his tone was almost electric in its intensity. The low notes, which he played with such authority, seemed to come from a contrabass. Though this proficiency was enough to make him co-principal cellist of the Bolshoi Theatre Orchestra, he will perhaps be best remembered as a promoter of Russian music and new works. He was the first to bring avant-garde composer John Cage to Soviet Russia, and in his recordings premiered many compositions, including those of Krzysztof Penderecki and Arvo Part. Perhaps most of all, Ivashkin was a fierce champion of composer Alfred Schnittke, recording his music (e.g. Schnittke’s “Cello Sonata No. 1” with Schnittke’s wife, Irina) and writing about his work and life. Ivashkin died in February at age 65.

Alice Herz-Sommer, pictured here at her debut in 1924, began learning Chopin’s etudes for piano in earnest after the Nazis invaded her homeland of Czechoslovakia in 1939. “They are very difficult,” she said of the musical pieces. “I thought if I learned to play them, they would save my life.” Four years later, in a concentration camp, she would be called upon to perform for fellow detainees and visiting members of the Red Cross. “These concerts, the people are sitting there — old people, desolated and ill — and they came to the concerts, and this music was for them our food,” she remembered. “Through making music, we were kept alive.” Herz-Sommer lost her mother to Terezin and her husband to Dachau. A Nazi officer, moved by her music, spared her and her little son, allowing them to stay in Theresienstadt until war’s end. She died in London this February, aged 110, the oldest survivor of the Holocaust. Near her life’s end, and in spite of such harrowing loss, she gave this summation: “Music is magic.”

Renowned Spanish flamenco guitarist Paco de Lucia was lost to the world on February 25. He was one of those rare traditionalists who can push a genre forward. “My father and all my brothers played guitar, so before I picked it up, before I could speak, I was listening,” he said in 1994. “Before I started to play, I knew every rhythm of the flamenco.” Having clear mastery of the flamenco form, with all its precision and passion, de Lucia started introducing elements of jazz, both harmonically and through new instrumentation. His first great musical partner was singer Carmen de la Isla, the two recording highly influential albums in the 1970s. The next decade saw even greater success when de Lucia collaborated with jazz guitarists John McLaughlin and Al DiMeola; their “Friday Night in San Francisco” sold more than a million copies. “Mediterranean Sundance” is de Lucia’s vehicle - a flamenco tour de force, augmented by the other two guitarists' dazzling ability. “What you do has to have credibility,” he said in 2004. “No matter how far you go harmonically, no matter how crazy it seems, it has to smell and sound like flamenco.”

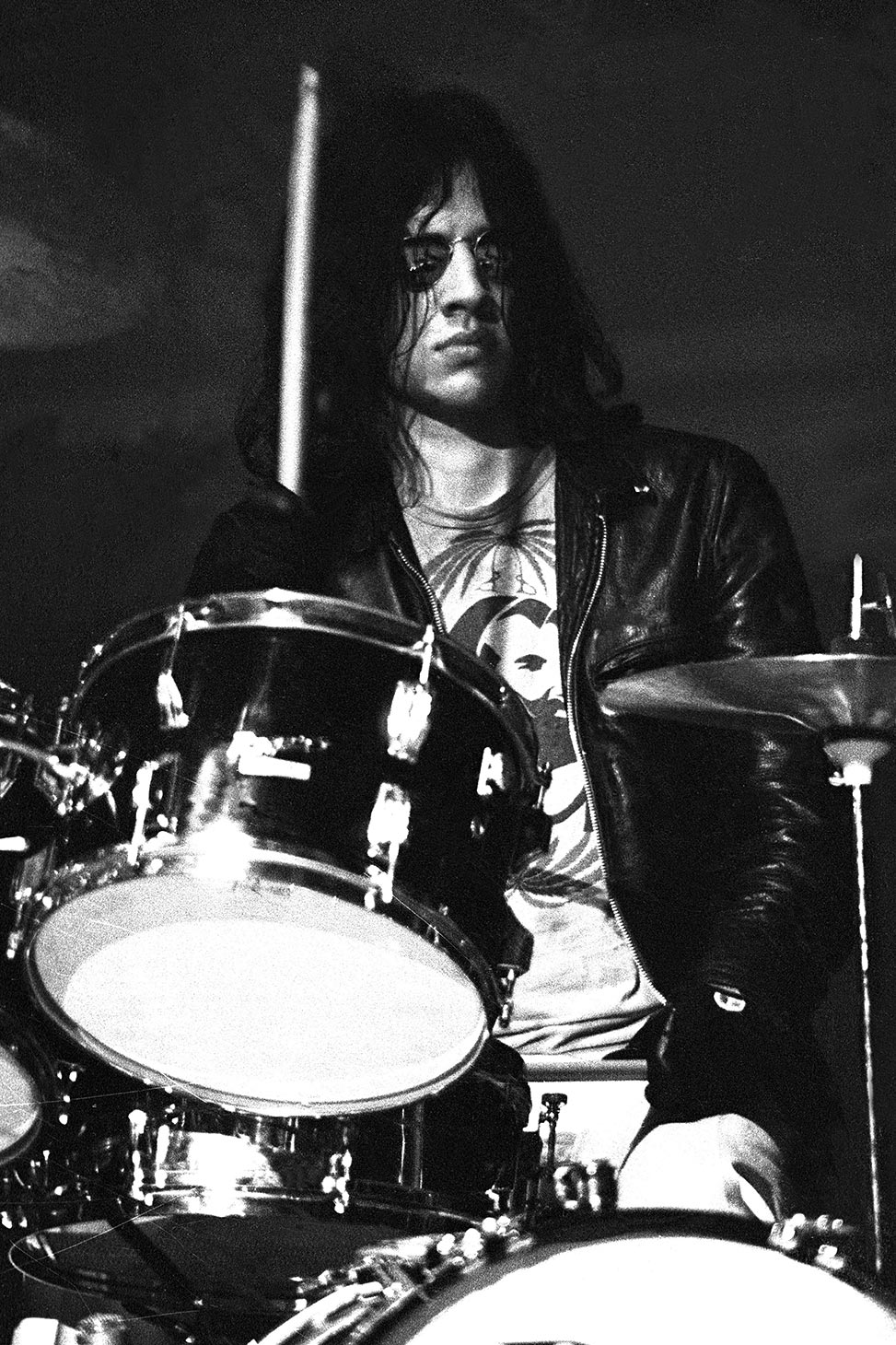

2014 was not a good year for pioneering punk drummers, evidenced not only by the passing of Tommy Ramone, but also by the death in March of the Stooges’ Scott “Rock Action” Asheton. He was 64. “Scott played drums with a boxer’s authority,” remembered his former band mate Iggy Pop. “He brought a swinging truth to the music he played and extreme musical honesty.” Iggy and the Stooges came roaring out of Detroit in the late 1960s and produced definitive albums like “Fun House” and “Raw Power,” playing an aggressive rock that replaced blues with a kind of Velvet Underground ferocity. As is typical of so many early Stooge’s songs, Asheton’s loping backbeat is the driving force of “I Wanna Be Your Dog”, even if it is mixed lower than the sleigh bells. Scott’s brother Ron, who played guitar in the group, died in 2009. “He played from inside the music,” remembered fellow musician Henry Rollins, “giving any song he played savage, unlimited power.”

James Ridout “Jesse” Winchester, a Louisiana native, moved to Canada in 1967 after receiving a letter from the draft board. He died on April 11 from bladder cancer. In between, he became a songwriter of significant influence, ultimately being covered by artists as varied as Elvis Costello, George Strait and Lucinda Williams. Winchester became a Canadian citizen in 1973, was pardoned by then-President Jimmy Carter in 1977, and moved back to the United States in 2002.

Throughout his career, Winchester maintained a gentle approach to his compositions, which he sang with a high, clear and lonesome tenor; in 1977 Rolling Stone called his “The Greatest Voice of the Decade.” “Nothing But A Breeze” is a fine example of the man’s mastery of form as well as his ability to be authoritative, even in vulnerability. Though never achieving much commercial success, he was one of those rare artists who inform and inspire other artists. So even if you’ve never heard Jesse Winchester, you’ve heard Jesse Winchester.

Herb Jeffries was more than the “Bronze Buckaroo,” a moniker he got as an actor playing black cowboys in the 1940s. He was also a singer of rare talent, moving from swing to bop with remarkable clarity and panache. Starting as a tenor, Jeffries shifted down to baritone on the advice of Duke Ellington’s arranger Billy Strayhorn. It was with Ellington’s band in the early 1940s that Jeffries recorded his first massive hit and signature song, “Flamingo”. He also appeared alongside Joe Turner and Dorothy Dandridge in Ellington’s musical revue “Jump for Joy.”

Jeffries began making movies in the late 1930s. “Little children of dark skin — not just Negroes, but Puerto Ricans, Mexicans, everybody of color — had no heroes in the movies,” he said in 1998. “I was glad to give them something to identify with.” His first picture was called “Harlem Rides the Range.”

Jeffries’ mother was of Irish descent, so his “color” was a matter of choice. “I just knew that my life would be more interesting as a black guy,” he told jazz critic Gary Giddins. Jeffries died in May.

In June we lost another great singer from the jazz age, this time James Victor “Little Jimmy” Scott. Scott was as far removed from Herb Jeffries, at least vocally, as is imaginable; due to a rare genetic condition, his voice stayed at a pre-pubescent contralto. Scott used this voice, once described by former bandmate Dexter Gordon as “neither male nor female but both at the same time,” to articulate an exquisite pain. It is a testament to the power and subtlety of Scott as a performer that he won the adoration of artists as varied as Lou Reed, Charlie Parker, Axl Rose, Frankie Valli, Madonna, Marvin Gaye and Ray Charles. His first hit, “Everybody’s Somebody’s Fool” was released in 1949, though Scott was not directly credited. Jazz Times called 1962’s “Falling In Love Is Wonderful” the “Holy Grail of jazz vocal albums.”

After a slump, Scott’s career was revived in the last two decades of his life. He appeared on David Lynch’s surreal television series “Twin Peaks,” as well as on Lou Reed’s 1992 album “Magic and Loss.” “I’ve been called a queer, a little girl, an old woman, a freak, and a fag,” he remembered. “As a singer, I’ve been criticized for sounding feminine. But I grew to see my affliction as my gift.”

It’s hard to describe the pure pleasure of a hearing the string bass played well: the thump of the attacking finger on the strings, the deep, woody resonance of the instrument’s hollow body. A good place to start is with Charlie Haden’s definitive version of Ornette Coleman’s “Lonely Woman”. The celestial rhythm section got a big shot in the arm in July, when Haden died. A solo artist for much of his career, Haden got his start with luminaries like Coleman and Keith Jarrett. In some live versions of Coleman compositions, Haden would quote a traditional country fiddle song. What would appear to be a jarring mash-up makes sense when you hear it, and even more sense when you know where Charlie Haden came from.

Haden was born in Iowa in 1937, a member of a musical family. His family played country music and so did he, debuting on the family radio show as a pint-size yodeler called Cowboy Charlie — that is, until he saw bebop pioneer Charlie Parker perform live in 1951. After that came Haden’s distinguished career as a sideman and leader, most notably with his own group Quartet West. In accordance with his left-leaning politics, he also formed the Liberation Music Orchestra, a unit that only released records during Republican administrations.

Charlie Haden exemplified what Duke Ellington meant when he said the best music was “beyond category.” “The beauty of it is that this music in from the earth of the country,” he said. “The old hillbilly music, along with gospel and spirituals and blues and jazz.”

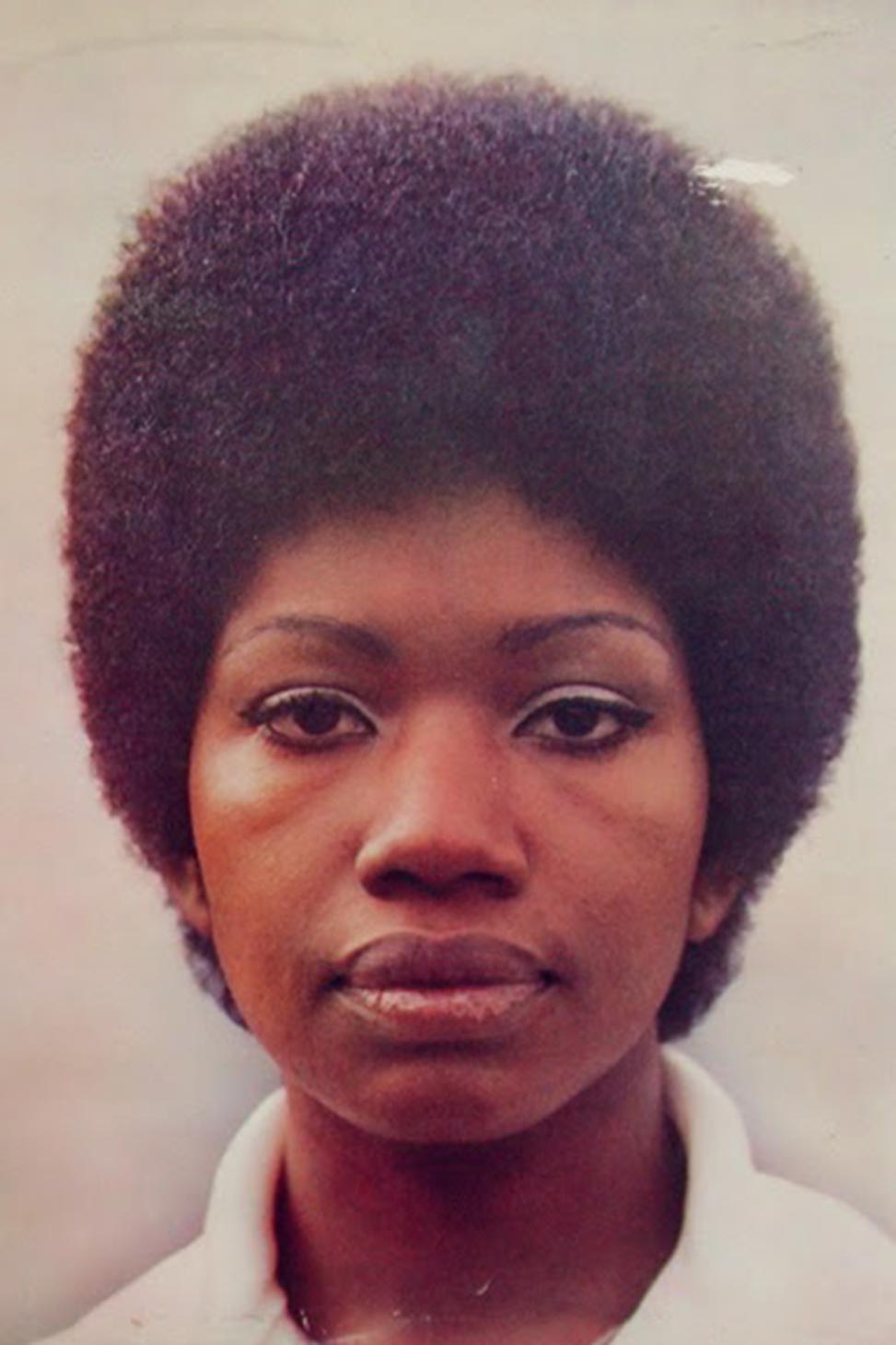

Rosetta Hightower had a direct and electric voice. It was first impressed upon the public consciousness in 1962 with “The Wah Watusi”, which she recorded with her girl group the Orlons. After a string of hits through the remainder of the decade, Hightower left to pursue a solo career, characterized by her gospel-inflected voice over deeply funky grooves. In the early 1970s, Hightower became a backing singer much in demand, appearing on Joe Cocker’s “With a Little Help From My Friends” album and John Lennon’s single “Power to the People.” She died on August 2, aged 70.

Electronic musician and producer Mark Bell died in October from complications after an operation. He was 43 years old. Along with Gez Varley, Bell formed LFO in 1988. Their sinewy, bass-heavy techno soon became integral to the rave scene. Bell extended his career by producing Bjork’s 1997 album “Homogenic” (e.g. “Immature”) He continued working with Bjork for many years afterward, as a DJ and sequencer. Bell’s producer credits also include Deltron and Depeche Mode.

“Rapper’s Delight”, released by the Sugarhill Gang in 1979, was one of the earliest and most successful rap songs. Henry Lee Jackson, who is on that record, died while being treated for cancer in November. Jackson was discovered rapping as he worked in a pizza restaurant in New Jersey, and auditioned for a recording contract by rapping along to songs played on a car stereo of an Oldsmobile 98. Once he and his friends were signed, Jackson rechristened himself Big Bank Hank.

The history of “Rapper’s Delight” is complicated. Recorded, possibly in one take, over the backing tracks of Chic’s “Good Times,” with rhymes largely borrowed from the Bronx’ Grandmaster Caz, the single supposedly sold in the millions but was never certified by its label. It’s still the Rosetta stone of the form, with catchphrases that made hits for other artists. “I mean one minute you’re walking down the street,” Hank remembered. “The next minute you’ve got bodyguards and being chased down the street.”

Claire Barry (here pictured on the left), an aesthetic world away from Big Bank Hank, also left us in November. She was 94. Wearing sequined couture, she and her sister Merna jazzed up Yiddish standards, backed by beautifully orchestrated swing or klezmer bands, in a career spanning decades. When the Andrews Sisters had a big hit with “Bei Mir Bist Du Schoen” in the 1930s, Claire and Merna changed their stage name from the Bagelman Sisters to the Barry Sisters and found broad appeal. They were enormously popular in Yiddish-speaking homes, in addition to appearing on the Ed Sullivan and Jack Paar shows and touring the Soviet Union in the late 1950s.

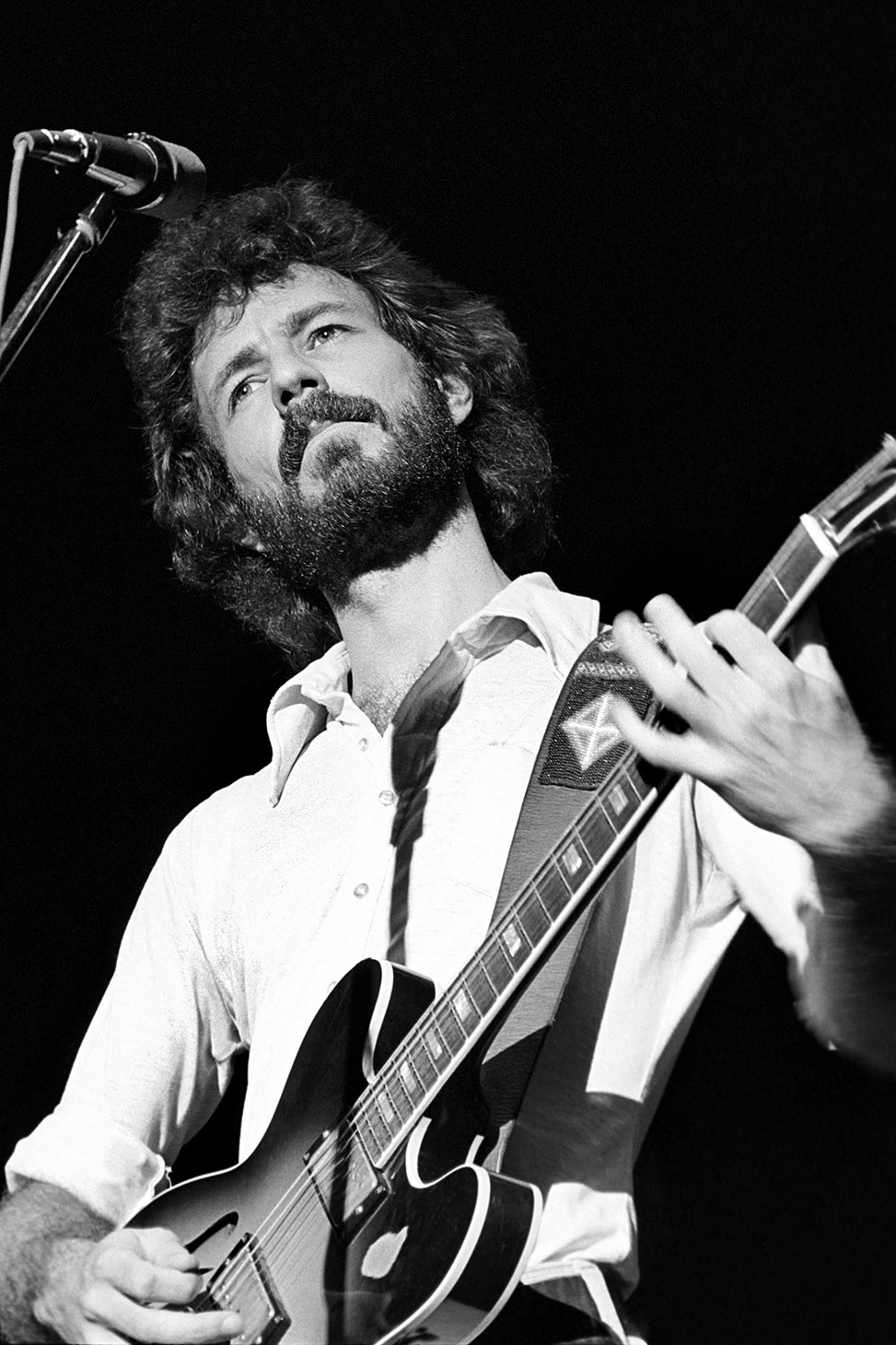

It may not have been Ian McLagan who first put a Wurlitzer electric piano on top of a Hammond B3 organ, occasionally playing both at the same time, but he did it best. McLagan’s work in the 1960s with British pop masters the Small Faces segued into success in the 1970s with the Faces, when Rod Stewart and Ron Wood stepped in to replace the departing Steve Marriott. He also accompanied practically everyone, from the Rolling Stones to Bob Dylan to Billy Bragg. An early and lifelong fan of American R&B and soul music — especially that of his hero Booker T of the MGs — McLagan was a reliably good time, as capable of nuance as he was of boozy bravado. His descending run in the Faces’ hit “Stay With Me” is second only to Ray Charles’ “What I’d Say” in the electric piano canon. McLagan died of a massive stroke this month. If one’s life can be judged by how he is remembered, the outpouring of pure affection for “Mac” after his passing is as much validation as could be hoped for.

Error

Sorry, your comment was not saved due to a technical problem. Please try again later or using a different browser.