The Cabula 12: Brazil’s police war against the black community

Brazil's anti-police movement continues to fight for the soul of Cabula, even as death threats intensify

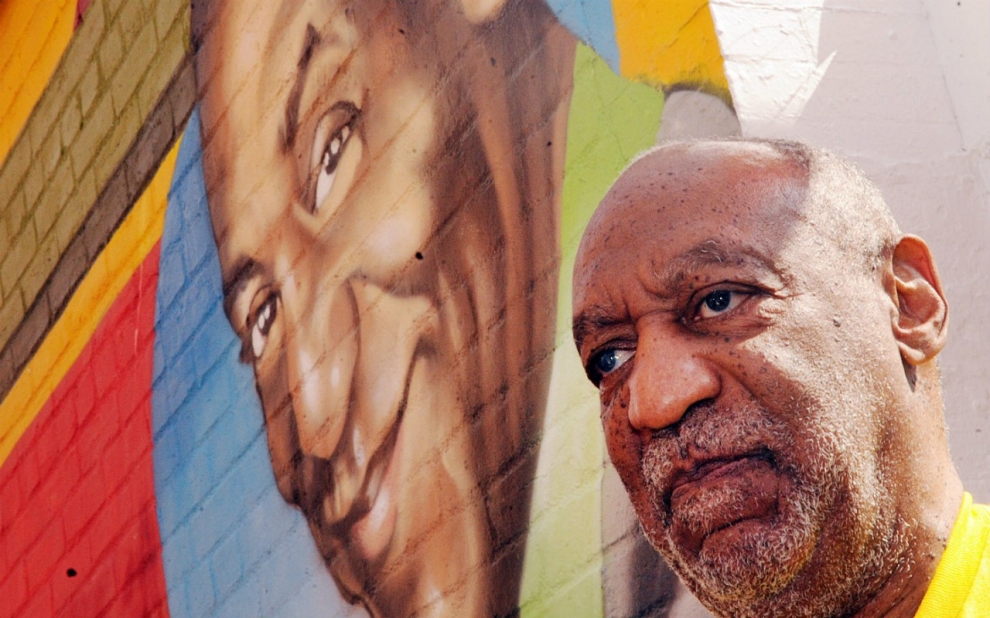

WASHINGTON — Along Washington, D.C.’s legendary U Street, Bill Cosby’s expression is hard to miss painted across the brick wall on the east side of Ben’s Chili Bowl, the greasy spoon renowned for its chili dogs. Other African-American heroes of the nation’s capital, such as President Barack Obama, Chuck Brown, the “godfather of Go-Go,” and radio host Donnie Simpson, join Cosby, but only the comedian’s face is totally rendered at street level. It’s a smirk that’s been burned into the American subconscious, whether from “The Cosby Show,” years of standup routines, commercials or his charitable pursuits.

“I wanted to capture the warmest feel, the warmest look for that particular mural,” says Aniekan Udofia, a popular D.C. street artist who produced the mural for Ben’s in 2012.

But the warm comfort that used to come from the grin of a man now labeled “America’s greatest serial rapist” is gone.

It’s been more than six months since 35 women appeared on the cover of New York Magazine, accusing Cosby of rape. Since then, he’s been arraigned on three felony charges of aggravated indecent assault tied to a 2004 accusation in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. (A defamation lawsuit from one of the women who have accused Cosby of assault, however, has been dismissed.)

Since comedian Hannibal Buress brought the Cosby allegations back to the forefront during an October 2014 standup routine, Cosby’s public fall from grace has been swift. An October 2015 YouGov poll crystallized the public’s feelings toward the comedian: Just 2 percent of Americans now hold a positive opinion of the man who played Cliff Huxtable.

The public backlash against Cosby, who remains innocent until proven guilty in a court of law, has been palpable. The Navy stripped him of his honorary title. Netflix cancelled an upcoming Cosby special. Numerous honorary degrees awarded to Cosby over decades have been rescinded, while other honors — such as his 2002 Presidential Medal of Freedom and his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame — either cannot or will not be revoked, despite public outcry. Last month, the Smithsonian shut down an exhibit funded by Cosby and his wife, citing a difficult debate about whether it was ethical for the institution to promote the exhibit.

The controversy comes at a time when the conversation surrounding sexual assault in America, and how to increase awareness around sexual violence, is at a fever pitch. It’s no different in D.C., where the rate at which rapes are reported has been climbing each year. Between 2011 and 2014, the number of rapes reported in Washington, D.C. increased by 173 percent, going from 172 in 2011 to 470 in 2014, the most recent year with available data, according to the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments.

Still, only one family and one man are allowed to eat for free at Ben’s. The family is the Obamas. The man is Cosby.

Cosby joked about his affinity for the restaurant at the opening of Ben’s restaurant in Arlington, Virginia, nearly two years ago, one of his last public appearances promoting the eatery,

“I want my body buried not far [at Arlington National Cemetery], so my ghost can get up [and] make the trip here instead of flying all the way over to U Street,” he said.

In D.C., the outcry has turned toward the mural that bears his grinning face, at the restaurant he’s been affiliated with for decades. From an online campaign calling for the removal of Cosby from the mural to a street artist’s decision to deface it, the growing movement against the Ben’s tribute has become one of the largest anti-Cosby campaigns in the country.

“For people who do walk by it and never noticed it before, it can be very jarring,” says Devin Boyle, one of the leaders of an online petition to remove Cosby from the mural. “It’s juxtaposed next to Obama … the president next to a man who now represents some pretty bad things.”

As Cosby's legend has grown, so has the lore surrounding Ben’s, which landed on the national map largely thanks to the endorsement of one of the most recognizable comedians in American history. On the restaurant’s website, Cosby is listed or pictured eight times in a historical timeline of important Ben’s moments — once more than Virginia Ali, the restaurant’s matriarch. Whether visiting the restaurant in 1983 or cutting the ribbon at the opening of Arlington, Virginia location more than two decades later, Cosby has been a constant presence in the establishment’s history.

So residents and activists wonder how Ben’s has been able to largely ignore — or at least not directly address — the Cosby allegations, along with concerns about how the mural’s meaning has changed.

“We’re very sympathetic about recent news,” Virginia Ali said during the July 2015 opening of a second Ben’s in D.C. “Very sympathetic, very saddened by all of that. But we’re focusing on opening our new store today.”

As the most recent wave of speculation concerning Cosby’s rape allegations now enters its third calendar year, the focus in D.C. has turned to his long relationship with the Ali family, and their loyalty toward him.

“There were periods in Ben’s Chili Bowl history where it wasn’t always doing so well as it is now. And he was there, championing the place,” Tim Carman, food writer and columnist for The Washington Post, told America Tonight. “In many ways, that long relationship [makes] it really difficult for the Ali family just to automatically let it go.”

He added: “The Ali family’s known him much more as a saint than they have as a monster. So how do you erase 40 years of viewing him as a close family friend?”

To better understand Ben’s place in history and why the mural means so much in terms of the restaurant’s relationship to Cosby, you have to go back to the beginning.

In 1956, Cosby — then in boot camp with the U.S. Navy near Bethesda, Maryland — would catch buses to D.C. for the weekend. A couple years into his service, Cosby, along with his friend Ronald “Stymie” Crockett, would make a habit of seeing some good jazz at one of the local clubs before getting a half-smoke or two at Ben’s. He wasn’t much for chili, but he loved hot dogs, and decided to give it a try. Not long after that, he took his future wife, Camille, then a freshman at the University of Maryland, to Ben’s for their sixth date. He’d later propose to her at the restaurant.

“I knew that I had the last piece of my perfect life,” Cosby wrote about his wife in the foreword for the book “Ben’s Chili Bowl: 50 Years of a Washington, D.C. Landmark.”

“I have always loved Ben’s Chili Bowl, and it has always been consistent. When I come to town, I want my half-smoke to taste the way I imagined it would … the way I remembered it. That is what Ben’s does.”

In the 1920s, U Street, the birthplace of Duke Ellington, became “Black Broadway,” an area of culture and great pride for the segregated African-American community in Washington, D.C. Seeing jazz legends — like Louis Armstrong, Miles Davis and Ella Fitzgerald — was a pretty regular occurrence down on U Street, home to a black middle-class that had disposable income to spend on entertainment. By 1958, Ben’s opened on U Street, and immediately became the heart of that Broadway. The chili spot, founded by Ben and Virginia Ali, was the place where people of color — Cosby included — could come to enjoy some fine food and music amid a period of cultural distress.

From then until now, it has been synonymous with D.C. The years following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., however, were tough on the neighborhood, with people of all backgrounds hurt by the tragedy, rioting and burning down the buildings around Ben’s. The outrage eventually culminated in the ugly riots of 1968.

“It survived the riots ... It survived recessions and everything else,” Carman told us. “It’s been like the Keith Richards of diners. It can survive anything.”

Ben’s kept going largely thanks to its founders: Ben Ali, a Trinidadian immigrant and Howard University alumnus, and his wife, Virginia. In a transient city where first families — and federal workers — come and go every four or eight years, the Ali family’s legacy is a constant. Ben’s remains a go-to attraction for locals and tourists alike.

“You can go into Ben’s Chili Bowl and you can have a doctor sitting next to a pimp, sitting next to a congressman, sitting next to a rapper, sitting next to a bus driver,” says Wes Felton, a D.C. actor and singer who has been Ben’s artist-in-residence for the last seven years. “There are not a lot of places — if any place — in Washington, D.C, in the past, present or future, where that kind of existence happens … It’s a place for everyone.”

Felton, 38, a native Washingtonian whose father, jazz musician Hilton Felton Jr., played at the Caverns decades before him, says he’s concerned about what the recent backlash toward Ben’s means for the future of artistic expression along the legendary strip.

“It’s about free speech,” Felton said last month as he rehearsed inside Bohemian Caverns, one of the U Street’s legendary music clubs that sits blocks away from the restaurant. He doesn’t think the Cosby portion of the mural should be taken down. “If we get used to the habit of being able to strike something down when it offends us, people will abuse that,” he said. “It’s a slippery slope.”

Tim Carman

Washington Post

Felton regularly hears from people about the mural, in person or over social media. He says the issue is polarizing — people either want to take it down immediately or feel that the mural has no effect on whether they’ll patronize a historical black business — with no middle group.

“I don’t think we have a right, as the public, to dictate [what happens]," he says. "We don’t."

According to one of the only polls done on the future of the mural, many Washingtonians seem to side with Felton. In a poll of 642 voters conducted by the FOX 5 DC before the start of 2016, 43 percent of those polled say that the Cosby portion of the mural should not be removed. Another 37 percent said it should; 20 percent said they weren’t sure.

POLL: Should Bill Cosby mural at Ben’s Chili Bowl in DC be removed? https://t.co/ZUPNjp2Hux

— FOX 5 DC (@fox5dc) December 30, 2015

Still, there’s no good indication what will come of one of the last remaining public tributes to the embattled comedian. In November 2014, Virginia Ali told the Washington City Paper that “Cosby is part of our family.” Last spring, in an interview with the Tom Joyner Morning Show, Virginia Ali again echoed the family’s support for their longtime friend.

“He’s part of the family,” she said at the time. “Absolutely.”

The “A” signature marks some of the more significant pieces of street art in the neighborhood, from the gagged George Washington at the intersection of 15th and U Streets or his take on Duke Ellington in Adams Morgan. At Ben’s, an “A” is located directly underneath Cosby’s chin. The “A” mark belongs to Udofia, the artist behind many of D.C.'s most notable street murals.

It’s a blustery January afternoon outside the U Street Metro station when we meet Udofia, calm and collected in a brown jacket, gray vest and silver hat with a purple feather. He’s one of the most established street artists in the area, but he’s humble; he keeps his head firmly in his work.

The 40-year-old takes a couple of drags of his cigarette before we head to the corner of 7th and S to see what he calls a “more positive” piece of work, offering a hint of the negative attention his once-heralded mural has received.

He tells us how this mural here, an interpretation of Marvin Gaye, might be his favorite. The iconic soul singer grew up a half-block from where we stand. The work is less than three years old, but the colors, and Gaye, who’s pictured hitting a note, are vibrant, as if they were just painted. Udofia’s work shows a rare style, capturing someone at an icon at the height of his powers.

“The murals shouldn’t just look like the people,” he says. “They have to have a soul to them; almost like the person is there.”

Born in D.C. but raised in Nigeria, Udofia grew up with a pencil in his hand, constantly sketching, always creating – despite his parents’ hopes that he’d become an engineer. Still, when he returned to D.C. in 1999, Udofia didn’t immediately take to the street art scene. Instead, he took on an odd assortment of jobs across the city, whether it be at a Burger King, as a security guard, or at a local CVS, which gave him more time to think and draw, over and over again. It wasn’t until he was making semi-regular trips to New York, door-stepping magazine offices looking for work, that he was able to break through.

Thirteen years later, he got a call he wasn’t expecting: The Ali family wanted Udofia to create a mural for Ben’s. It was a moment Udofia, overcome with joy, would come to recognize as a pivotal one in his career.

“I still remember the nostalgia [of Ben’s],” he says. “It was just exciting. I remember telling people, ‘Wow.’ I had this childlike excitement when I was called upon to do the mural.”

As the allegations began to hit new highs last year, the outlook toward the Cosby portion of the mural began to sour quickly. With neither Cosby nor the Ali family making any public comment on the future of the mural, the public reaction has been redirected toward Udofia, with people both online and in person, he says, asking, begging and even harassing him to do something about the piece.

The artist should take it down.

The artist should have considered that before he painted it.

“Since the allegations, of course people have a lot of mixed feelings now about Bill Cosby,” he says. “I think of a lot of people kind of feel like [the mural] is the artist’s responsibility.”

Udofia has taken it in stride, recognizing the delicate nature of the situation as well as the big-picture issue of sexual assault in America. But he’s also stood firm, not injecting his opinion on whether the work should come down and leaving the final decision to the Ali family. He says he thinks of himself like a tattoo artist with a customer who wants to remove a tattoo he gave them; in the end, it’s what the customer wants, not the artist.

“I was commissioned to do a mural, and what I do is I do it to the best of my ability,” he says. “So, at this point, it’s not really my responsibility. It’s more of the responsibility of Ben’s Chili Bowl since they commissioned it. I am quite open to any changes, or decisions about changing the mural that might come about, because my aim is to create work that is appealing to the communities that they are in.”

Aniekan Udofia

The Ali family did not return multiple requests for comment for this story.

Inside Udofia’s studio apartment in Adams Morgan, his living space doubles as his workspace. Stacks of books, CDs, paint cans, paint sprays and paintbrushes take up a lot of the space in what was once his living room. Dozens of sketches of cultural giants, finished products and works in progress, cover the walls: Gaye, the Notorious B.I.G., Ol’ Dirty Bastard, Maya Angelou and Bruce Lee. He sits down on his stool, locked in on his latest project, pushing his paintbrush back and forth in an almost rhythmic motion. It’s a quiet space that allows him to reflect on how far he’s come — and how he doesn’t want to be defined by a face that takes up just one-fourth of one mural.

“I’ve done a lot of work around the city, and I don’t want [my work] to be narrowed down to just one person,” Udofia tells us. “The mural is not the Bill Cosby mural. It’s the Ben’s Chili Bowl mural … and the concept and composition of this mural was done with everything positive in mind.”

Every time Devin Boyle walks or drives by Ben’s on U Street, she can’t help but give the mural the double middle finger. She’s not doing it for attention and it’s not directed at Ben’s, as she thinks the restaurant doesn’t deserve to be flipped off every time she passes by. Yet, months after the New York Magazine cover, her reaction toward Cosby hasn’t changed.

“The man has done, or allegedly done, terrible things,” says Boyle, one of the more vocal leaders pushing for the removal of the mural. “I have to say, ‘F--k you, Bill Cosby.’”

In October, Boyle, the 31-year-old director of media relations for Collaborative Communications, a D.C. public relations firm, penned an editorial for the Washington Post, outlining why maintaining the mural would send the wrong message about how we respond to sexual assault allegations across America.

“What example are we setting if we allow a piece of ‘public art’ of his smiling face to remain for the world to see?” wrote Boyle in the Post.

Shortly afterward, Boyle helped launch a MoveOn petition, calling for the removal of Cosby from the mural. The comments, which came from people throughout the U.S., were filled with venom toward both Cosby and Ben’s:

We are sick of this rapist being honored on the outside while being so disgusting on the inside.

As long as Bill Cosby’s face is still on the side of the building, Ben’s won’t get a dime of my family’s money. I cannot, in good consious [sic], support a business that defends a serial rapist like Bill Cosby.

The continued existence of Cosby’s mural — facing … Barack Obama, no less — is a reminder that rape victims too often remain the punch line of jokes…Shame on you, Ben’s Chili Bowl, for deifying a demon.

But as time has gone on, the once fired-up group of petitioners has lost steam and the online campaign has petered out, stalling out at 230 signatures. That still hasn’t stopped other forms of pushback. After the op-ed and launch of the online petition, Smear Leader, an anonymous street artist known for marking parts of D.C. with stickers of North Korean dictator Kim Jong-Un, planted a sticker of the dictator over Cosby’s mural face.

Boyle, who says she didn’t think defacing the mural was the best way to start a conversation with Ben’s about scrubbing Cosby from it, is still hoping that Cosby’s place, next to three black legends in D.C. history, will be painted over with another story, out of respect for women.

“The meaning [of the mural] has changed, and because of that, I think it should be removed,” she says. “It doesn’t mean the same thing.”

One variable that could inevitably force the Cosby portion of the mural to be altered is whether Cosby is convicted in the Pennsylvania case — charges that his lawyers have filed a motion to dismiss. (Editor's note: Hours after this story was published, a Montgomery County judge rejected Cosby's motion to dismiss the case.)

“If he gets convicted, that could push their hand,” says Carman, who notes that Cosby not being at the July 2015 opening of a second Ben's in D.C. is a sign that the family could be starting to back away from Cosby.

But until the comedian is convicted, no one knows for sure if or when Ben’s will publicly address Cosby and the future of a mural — allowing his smirk to stay on U Street for all to see.

“We’re talking about a mural that is part of history," Felton says. "What [the family] chooses to do about the mural is their business. It’s family business.”

Brazil's anti-police movement continues to fight for the soul of Cabula, even as death threats intensify

More than 2.5 million children in America have a parent in prison; they told us how they cope.

The NCAA knows even less about concussions among women than it does about those among men; will that change?

America Tonight speaks with women on either side of the controversial movement

Error

Sorry, your comment was not saved due to a technical problem. Please try again later or using a different browser.